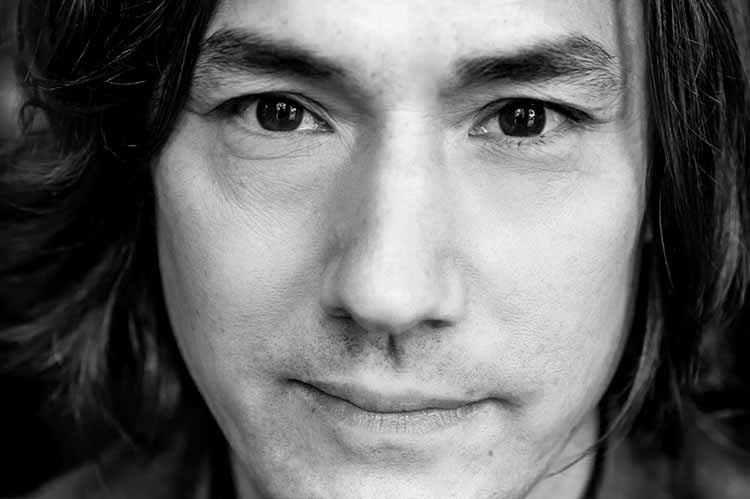

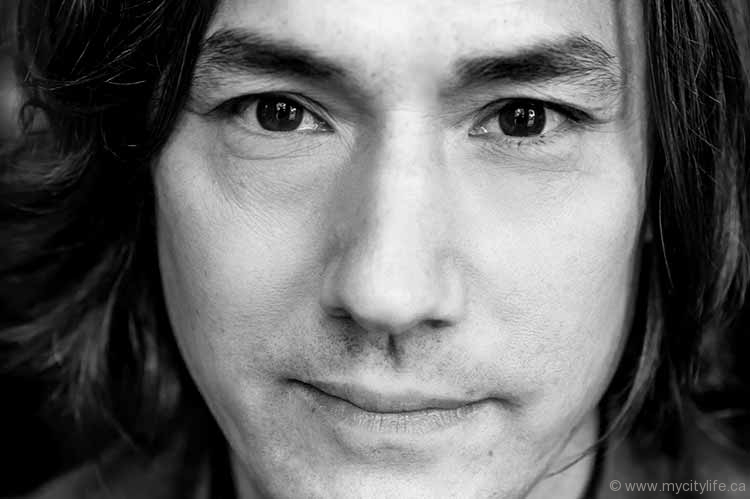

David Usher — Recapturing The Creative Spark

Singer-songwriter, entrepreneur and keynote speaker David Usher has come out with a new book on unlocking your creativity, one that will change the way you view your own abilities and the creative process. And City Life has the first interview

David Usher wants you to write in his book. Go ahead: jot notes, doodle pictures, scribble thoughts. He doesn’t mind. “When I started thinking about making a book about creativity, about the creative process, I wanted the book itself to be, in many ways, an artifact that was creative in form as well as function,” says Usher of his first book, Let the Elephants Run, over the phone from his home in Montreal. “I believe that creativity is an action-based activity. You have to do stuff to make it happen.”

And Usher should know. The Canadian singer-songwriter has been professionally making music for over 20 years, as both the frontman of alternative rock band Moist and in his own solo career. Over those two decades he’s sold more than 1.4 million albums and nabbed a number of awards, including five Junos. He’s also the founder of his own company, CloudID Creativity Labs, which develops innovative projects, such as web platforms, and does creative consulting for clients that include Cirque du Soleil and the Toronto International Film Festival. And from time to time he’s also giving keynote speeches on the creative process. You may look at a guy like David Usher and think he was lucky. He was born with this gift for creativity, endowed with some divine gift for making art and tech and other things that only the blessed creative-types of the world can. Creativity is something he has and most of the rest of don’t. Right?

Wrong.

“People often at conferences come up to me and they really do say, ‘I wish I could be creative.’ You are creative,” says Usher, 48. “But maybe you’re just not exercising that side of your personality.”

Which is exactly what Let the Elephants Run aims to do: help readers to break free from the patterns and conventions of everyday life, and to exercise their creative muscles, harness that reinvigorated creative energy and make it productive. Usher believes we all have that “creative gene,” that creativity is a skill that can be tapped into and honed just like any other. “Stop looking at creativity as the lottery that someone else won at birth,” Usher writes. “Start looking at creative thinking as a skill set that you can master if you invest the time to learn how.”

Through the text, Usher outlines the journey of his own creative process to show how he gets from conception to the finish line. He suggests “Actions” to get our creative juices flowing. He talks about the process of filing and filtering ideas, and then experimenting with those ideas to find those “creative collisons.” As it’s a book about creativity, the design is highly creative as well. There are many images and graphics to illustrate points, and certain pages, coloured using eye-catching palettes, are dedicated to single pieces of advice, telling us, “In this new fast-moving, ever-changing environment, creativity is not a luxury or a risk. It really is a necessity,” and, “If an idea falls in the forest and no one sees or hears it, did it ever really exist?” and, “If you think you are not creative, ask yourself how much time you have actually devoted to the pursuit of creativity.”

There’s a real artistic quality to it, but it’s also very direct and easily digestible, which is part of Usher’s plan. “There’s a reason why you need to have a physical copy, because I’ve tried to make it into something you need to look through and touch and write in and feel,” he says. “I wanted the language to be straightforward, because I think that there is a tendency to make creativity seem mystical.”

While he acknowledges that there is a “magic to moments within the creative process,” Usher dispels the mysticism by directing our gaze to the work involved — the persistent, time-consuming, grinding work. Take his song, “St. Lawrence River.” It took him a year to write and he estimates it went through 30 different choruses. As he writes, “creativity is 95 percent work and discipline, and just 5 percent inspiration.”

The idea for writing Let the Elephants Run began fermenting in 2012 after he wrote a blog for the Huffington Post titled “The Perfect Time to Get Creative is Now” (which is also featured in this book). In it he outlines how creatives don’t live idealized lives where they always have the perfect space with ample, uninterrupted time to work. Usher is married to interdisciplinary theatre artist Sabrina Reeves and the couple has two daughters, Coco and Océane. As any parent knows, kids need attention. A lot of it. Compound that with our modern “distraction economy” where everything — TV, Facebook, our phones — vies for our attention and it becomes crucial to “define a methodology” and find ways of fitting the creative process into our lives. Even if that means waking at 5 a.m. before the kids start running and screaming around the house.

After writing the Huffington Post piece, and doing speaking engagements, he started to realize that he wanted to dig deeper into the material and figure out how he engages with the creative process. He began to write in the spare time between recording the new Moist album, playing shows and giving keynotes, which suits his style. “I probably can’t write for more than 20 minutes at a time,” he explains. “I’ve got a little ADD in that way, where I work on many different projects and I’ll flip between them.” But once he finds a direction and gets his claws sunk in, “then I’m just continually collecting. I’m seeing all sorts of reflections of that idea in all sorts of different places, collecting those ideas and then writing them down.”

Usher is constantly taking notes of things he sees, hears and experiences. “Artist or entrepreneur, in my mind we are all hustlers and thieves. We are an amalgamation of the ideas that surround us,” he writes. “We absorb and steal, rob and plunder — whatever it takes to get our creativity moving.” Which is true: so much of the art and tech that we love is based on ideas of others. Star Wars, for example, is heavily influenced by Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress.

Even Usher’s “Black Black Heart” arose from his attraction to the drum and bass line of Eminem’s “Stan” and an opera sample from Lakmé, the “Flower Duet,” by his friend Jeff Pearce. He wasn’t a fan of Eminem’s “misogynistic and homophobic lyrics” and Lakmé wasn’t part of his “musical vocabulary.” But being open to those experiences, he was able to write one of his most popular songs.

“Those are often where great ideas come from, where great sparks come from — things outside of our genre, outside of what we normally do,” Usher says. “If you hate rock music, and you go to a rock show, you might hate the concert but you might love the lights.”

To further illustrate the importance of openness, Usher scatters famous quotes from a variety of individuals from a range of industries and arts. “I find that there’s a massive similarity between creativity in the arts and creativity in the startup culture,” he explains. On one page, a quote from Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast; on another, one from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations; and on another still, a lyric by Macklemore. “Ideas are everywhere and they may not naturally fit together but there’s something in these ideas,” he says. “They don’t come from naturally occurring places but they sort of fit together.”

One of his favourite quotes is by Silicon Valley entrepreneur and academic Steve Blank: “Business plans rarely survive first contact with customers. As the boxer Mike Tyson once said about his opponents’ prefight strategies: ‘Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.’”

It’s another lesson fledgling creatives need to remember: “Failure and getting knocked around and getting rejection is a big part of creativity. You’ve got to have a really thick skin.”

Usher describes a time when he took a major metaphorical fist to the face when he was the co-founder of a social media aggregation startup right after Twitter launched. They were working on aggregated streams on the iPhone, on the Adobe Air app and as an iframe on the web, but “ran out of runway” and the project never made it off the ground. It was intense and heartbreaking, but in that pain there’s a lesson.

“I think it helps to be aware that every time you smash into a wall, there’s a period of pain. And experience teaches you that that generally goes away pretty quick, and if you’re open to it, you can really learn from those experiences.” And if you’re not “crashing into walls” and failing, “it probably means you’re not reaching high enough.”

At one point, you’re going to have to reveal your idea to others, but it’s important to reveal them to the right people. Ideas are fragile in the early stages and can easily be stamped out by doubt. Usher says it’s important to have “reflectors,” people who can offer insight and help you see things in a new light. Usher’s friend Mitch Joel, author of Six Pixels of Separation and Ctrl Alt Delete, has been one of his biggest reflectors. Joel “will take your ideas and bounce them back at you and you will see angles to them that you never saw before.”

While we often might look for reflections in those closest to us, that’s not necessarily the best place to find them. “I think you want to find people that are smarter than you are,” says Usher. “I don’t want someone to tell me something I already know. I want them to tell me something I hadn’t thought of at all, so I can steal that,” he adds with a laugh.

Motivation is also important to the creative process. As he writes, “If you stop, you exponentially increase the chances that you will never get to the finish line.” Creativity, he says, is like a wave. Each wave pushes you forward, leading to the next idea, and then the next and then the next. When working on a project, Usher tries to do something on it every day, even if it’s just an email or a phone call — anything to keep the wave going. “You are constantly trying to keep a momentum going and at the same time not give up and get to what you hope is the end,” he says.

When it’s all said and done, Usher wants readers to realize that there really is no secret to being creative. By revealing the “nuts and bolts” of the process, he hopes personal doubters will understand that the creative process is just a series of small steps over a long period of time, building toward a goal. “We really all can do it. It’s just getting down to doing it,” he says. “You do one thing today, one thing tomorrow, and you just keep doing it, and suddenly, a year later, you’ll find yourself in a new place.”

Maybe that new place will be a painting of a child playing in a winter landscape, or a novel about a teenage heroine trying to track down the thieves who stole her deceased grandfather’s war medals, or a social media app that encourages users to help others identify the unknown items featured in posted photos.

Does that give you any ideas? Well, feel free to write them in Usher’s book. He won’t mind.

David Usher’s Let the Elephants Run will be released on March 7.

www.davidusher.com

@davidusher

No Comment