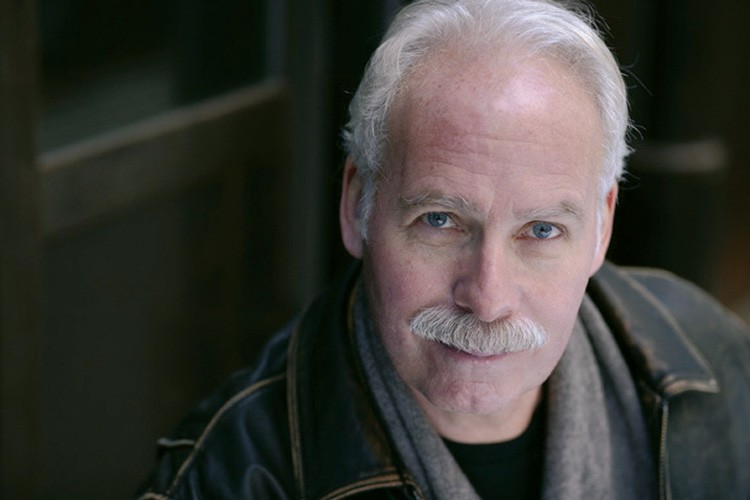

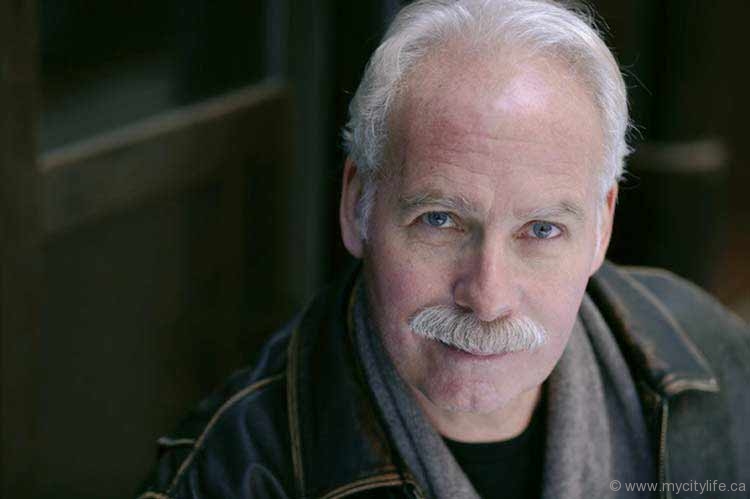

Trapped in the Arctic’s Killing Ice

How a perilous journey through the Northwest Passage brought reconciliation to a father and his children

For the better part of the 18 hours I’d spent at the helm, we’d only made about five kilometres total. Ship-killing ice was moving down from the north, forcing us into a wall of equally dangerous ice to the south. The sea floor of the Arctic’s Northwest Passage is littered with the crushed carcasses of hundreds of ships and perhaps twice as many men who, during the past few hundred years, tried to accomplish what I was trying to do: find and cross the Arctic Grail, the theoretical shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Just a few hours before, I was happy to gain 150 metres; now I was praying that Bagan, my 57-foot trawler, would gain a precious few more to keep her from her impending fate of total destruction.

Three years earlier I’d come up with the idea to travel to the Arctic to make a documentary about the Passage and the nearly 14,000-km journey from Rhode Island to Seattle. As risky and deadly as the idea was, it was something I could handle. But as Bagan became more and more hopelessly stuck in the six-foot-thick ice sheets, one thought repeated in my exhausted mind: “Have I reunited my children only to lead them to their deaths?”

As a filmmaker and professional sailor with nearly 65,000 offshore kilometres, I had always toyed with the thought of finding the Passage and perhaps carving out a film about the hunt for it, and about something that’s on everyone’s minds these days: climate change. After years of debating the merits of such a trip, the fateful day came in December of 2006 when I realized that I had the boat, could find the crew, could probably find the funding and that there was no time like the present. For almost a year everything fell nicely into place — until things started falling to pieces. Due to the economic crisis of 2008, three months before we left for the Passage I lost every penny of financing. A crippling blow, for sure, but I had already put in enough of my own money that I couldn’t afford to back out. I believed in my dream project but also realized that unless a miracle occurred I’d be paying off the cost of it for the rest of my life.

Throughout my years I’ve found that one of the wonderful things about life is that if and when miracles come, they are seldom what you expect. Shortly before I lost my funding, the trip and my life took one of the most powerful and abrupt turns I’ve ever experienced.

Fifteen years prior I was living in California with my two stepchildren, son and then-wife. Sadly, we didn’t survive as a family and went through a divorce — which seemingly happens more often than not these days. Both my ex-wife and I tried as hard as we could to make a bad situation tolerable, but as any parent knows, it’s never enough. Because of hurt and anger, I slowly lost contact with my stepson, Chauncey, and had only partial contact with my stepdaughter, Dominique. But my son, Sefton, and I managed to see one another many times a year. They lived on the east coast and I on the west, and despite daily phone calls, it seemed an insurmountable distance both physically and emotionally.

When the idea of the Arctic trip came up I made sure that Dominique and Sefton knew about it. I didn’t know what or how much Chauncey knew, for at that time we weren’t in each other’s lives. I hoped Dominique and Sefton would join the trip, but Sefton had college commitments and Dominique wasn’t 100 per cent sure that she could. Yet around four months before Bagan departed, the miraculous unfolded. Dominique was able to commit full-time, Sefton got a waiver from college for the semester, and after at least 12 years of silence Chauncey got in touch, asking if there was room aboard. For the first time in a decade and a half, all four of us were going to be together, all under one very small roof and attempting to travel through one of the world’s most unforgiving but spectacular areas. It would be five months and almost 14,000 km of living in extremely tight quarters in which anything could and most probably would happen. So with my family and two other hand-picked crew members, the six of us headed out and into the Arctic, hoping to do what explorers have tried to accomplish since the days of Columbus: find and transit the Northwest Passage.

What occurred during those five months was staggering, something that to this day my kids and I still have trouble believing. Despite the presence of a very large “elephant in the room” — the unanswered questions, untold hurts and unspoken mistrusts hanging over our heads — we very quickly and assuredly came back together as a family. Due to the tremendous physical and mental challenges, we didn’t have the luxury of time for a post-mortem about what had happened 15 years earlier. We very quickly found out who we are now and didn’t reflect on who we were then. We all found ourselves in the trenches together and had to trust each other and have each other’s backs, which we did time and again. Certainly we compared notes about long ago, and many times played “remember when … ?” But the hurt and pain couldn’t stand up to the love and support we carried deep inside — love and support that, due to the demands of the trip, grew daily. We spent many hours talking about the future, what it held for not only each one of us, but for us as a family. What had happened — the divorce — was “then,” and this was “now.” We were back together as a unit and would have many, many years to discuss the past if we wanted to. I have never known the sort of pride, admiration and love I felt when I saw how my kids, now grown adults, came together in moments of horrendous weather and circumstances, and none more amazing than the three days we were trapped in the Arctic’s killing ice.

Once in the Passage proper, we headed south down the wide channel of Peel Sound. We waited for the semi-permanent ice to clear in the Central Channel, the southern part of Peel Sound, for over a week, all the while keeping an eye on the northern part of the channel, our escape route. Three times a day we downloaded ice charts from the Canadian Ice Service, trying to follow their predictions as to what the ice to the south of us was going to do and if there’d be a small opening that would allow us through. Day after day we saw no hint of such an opening forming, and finally the day came when the chart told us what we desperately needed to know. We would be able to move down through Peel Sound, exit the bottom of it and head to the west.

We left early that morning and set out to find the break in the ice the charts promised. After five hours of pacing back and forth along the northern border of the ice, however, we found no opening and no sign of a potential one. We decide to head back to the safety of the anchorage where we had just spent the past week, and wait some more.

Were it only that simple.

Just to the north, and heading south down Peel Sound, was an ice field perhaps 30 km long and at least 3 m thick. By the time we found it, it was well past our safe anchorage. With the stationary ice to the south of us and the approaching ice to the north, we were in a deadly squeeze play, just like the type that had killed so many hundreds of men and ships before.

It only took a few hours for the ice to get us. It locked us in with Herculean strength and, regardless of what we tried, we couldn’t move an inch. Bagan was trapped and slightly canted up on her starboard side. Hidden and uncharted underwater currents slowly but inexorably drove us up and onto a rock-bound shoreline. We were all out of options. As far as I was concerned this was the start of the final deadly chapter in our family’s new life. We were in 24-hour daylight, so we were spared the horrors of darkness. But day or night, the sounds of the ice clawing its way past our hull were nothing short of banshees’ wails. Screeching, ripping, shattering sheets of ice squeezed Bagan until even she wailed in protest. Several times I sent Sefton below to pull floorboards and see if our hull had been breached and if we were taking on the Arctic’s freezing water.

Yet as horrific as the situation was, my sense of love and pride at seeing how my kids handled it was beyond description. No one was in denial as to what could happen, and I’m sure that we all nursed hidden fears, but with the task at hand none were shared publicly. Instead, we endured three days of what the Arctic threw at us in a calm, serious and logical manner. There was even laughter to be heard. During that time I have never been more proud or more honoured to be with three people. I’m firmly convinced that this level of maturity and care could only have been reached through the love we had all started to find at the beginning of the trip.

We eventually made it to Seattle but not without other terrifying incidents. With each and every one I saw again what I saw those days in the ice: three grown “pros” who not only had each other’s backs but each other’s hearts as well. After the trip ended, Sefton, Dominique and Chauncey went their separate ways and continued to do what they were doing prior to departure. We are all closer to one another than ever, now a new “old” family unit — one that survived not only the Arctic but also the challenges of reuniting a loving and caring family that had seemingly only “taken a break” for 15 years.

Guest Travel Editor

Sprague Theobald is an Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker, author and seasoned sailor based out of Manhattan, New York. Through his company Hole In The Wall Productions, he’s travelled from Alaska to Zanzibar, and his writing has been featured in the New York Times. His journey through the Northwest Passage was documented in the book and documentary film The Other Side of the Ice.

www.spraguetheobald.com

No Comment