Sarah Milroy: Rebalancing The Narrative

The McMichael’s chief curator on growing up in Vancouver, ignorance and why the gallery’s upcoming exhibition, Uninvited, is a behemoth for upholding the artistic accomplishments of women.

Growing up, Sarah Milroy was never far from art. Her mother, Elizabeth Nichol, started Vancouver’s Equinox Gallery with a vision to combine the best of contemporary Canadian and international art. Her house was home to pieces by Andy Warhol, David Hockney and Canadian artists, including Jack Bush and E.J. Hughes, as well as early memories of swimming at British Columbia’s Savary Island and bear cubs making their way into the garden.

It was in this atmosphere — where she had to explain to her friends why there was such thought-provoking work lining the walls — that Milroy savoured her first taste of talking about art. “My mother created this highly charged space where people could come together and would always have questions,” she says. “It was a lovely place to grow up.”

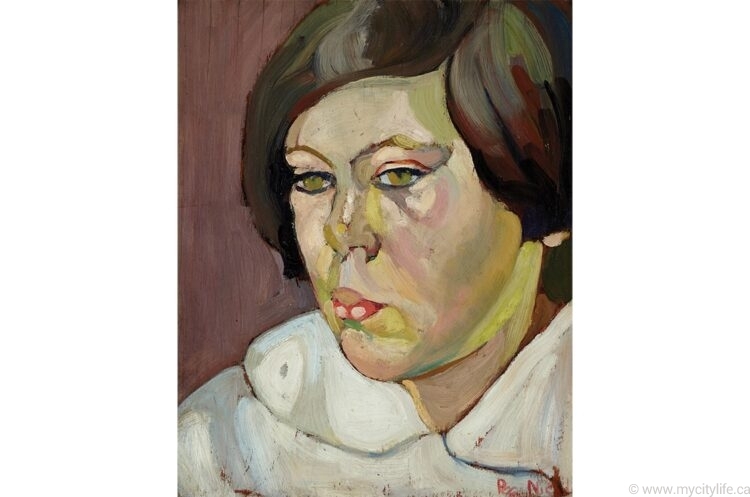

From there, Milroy studied English literature at McGill University and Cambridge University and then obtained a master’s in art history at Hunter College in New York City. Originally, she planned to be a teacher, but after an exhibition of Paraskeva Clark’s work in Halifax (who incidentally features on the cover of the book that the McMichael is about to publish), Milroy knew her future held a career in art. “She had a very special place in my life, because she was the ‘on’ switch,” Milroy says. “I saw this show, and her paintings were all about social issues and the city. They had portraits, and it was historical Canadian art, but not about landscape. I was struck by that.”

After writing about the exhibition for Canadian Forum, which is a literary, cultural and political publication, she moved to Toronto and started writing for Canadian Art magazine as assistant editor, then associate editor, and eventually became chief art critic at The Globe and Mail. “I always thought my focus would be around writing and literature, but it’s turned out my career’s been about writing about art.” Milroy is driven by education and learning, and she believes that the more she learns, the more ignorant she feels. “There are so many stories and wonderful people to study, both living and long gone,” she says. “So many connections between historic artists. It makes me feel quite frantic.”

Today, Milroy is chief curator at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, a Kleinburg, Ont.-based gallery that began when Robert and Signe McMichael began collecting art in their home. As well as answering endless emails and researching artists and their work, Milroy and the museum are working diligently to widen the collection. “We’re working hard to diversify historical holdings, buy work from contemporary living women and bring BIPOC [black, Indigenous and people of colour] voices into the collection,” she says. “We’re trying to rebalance the narrative that the McMichael can tell about what Canada is and where it comes from.”

Alongside her involvement in the industry, Milroy’s mother believed there’s no such thing as a stupid question and set out to create spaces that were welcoming, where artists and patrons could come together as equals. It’s something that was inspirational for Milroy and drives the atmosphere for which the McMichael is known.

“There was a real feeling of solidarity with the artist at her gallery and a dignity and importance around what they did. She set a tone of respect and pleasure, where people could talk freely and be relaxed. That’s something I try to emulate,” she continues. “The McMichael is an informal place. It started as a home and then it grew, so it retains a lot of the feeling and hospitality of a home. We want to create a sense of homecoming and a safe space for people to explore different cultures and ways of looking at history and Canadian identity.”

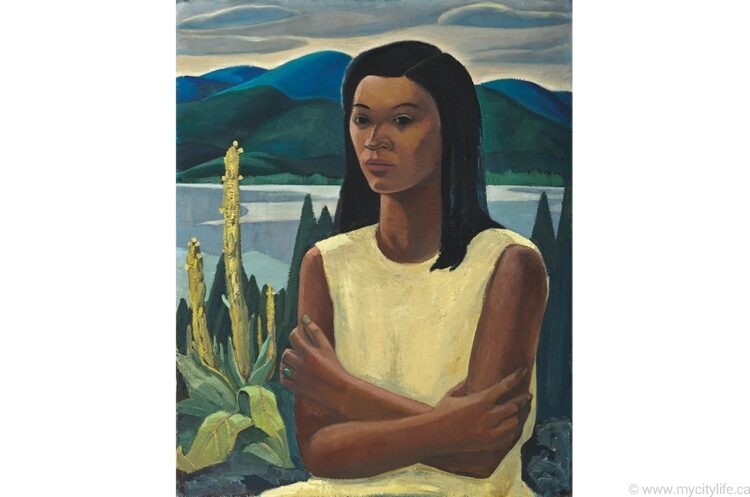

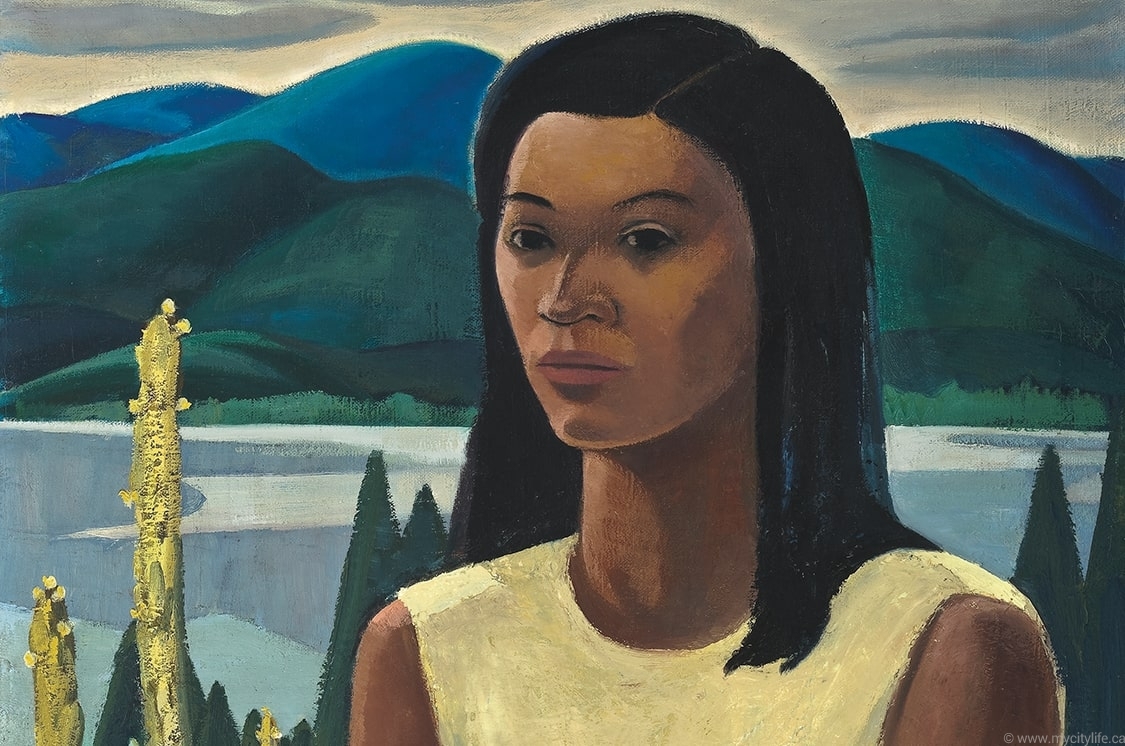

The McMichael’s latest exhibition, Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment, is set to open on Sept. 9. Featuring more than 200 pieces of art by women painters, photographers, sculptors, architects and filmmakers, it’s described as “a monument to the talent of Canadian women artists in the interwar period.”

“What we’ve pulled together here is thunderous,” Milroy shares. “The catalogue has 40 essays in it. There are artists from all across Canada, including settlers and Indigenous women, and immigrants making careers in Canada in that 1920–45 period. That’s the period of Canadian art that’s dominated by the Group of Seven and landscape painting. This exhibition is a massive correction, showing the dark side of the moon.”

“We’re trying to rebalance the narrative that the McMichael can tell about what Canada is and where it comes from”

Milroy is also hoping it’s an exhibition that will prompt people to reach out and connect with the museum about pieces held in families that could eventually find a home at the McMichael. “We have 6,000 works in our collection,” she explains. “By museum standards, it’s small. It’s good but focused. Everything we bring in gets used. We really put our conscience on display. We rotate regularly. We lend liberally to colleagues, so nothing is wasted.”

The exhibition is set to be next in a number of successes in Milroy’s life. In 2020, for her role in promoting Canadian art and artists, she was made a Member of the Order of Canada. She describes getting the call a “total shock,” not just because it’s unusual for someone in her profession to get the award, but also because it spoke to the legacy of her father, John Nichol. As a Liberal politician and senator who served in the Second World War, Milroy saw the award connecting to the passion he had for his country. “He loved B.C., and he really loved his country,” she says. “I feel I get that part from my father, and the art part from my mum.”

But for all the successes that Milroy has experienced, her defining moment to date was the opening of the U.K.’s first exhibition dedicated to Canadian artist Emily Carr at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery. “That show in London included historic work from the collections of the British Museum, National Museum of Scotland, Pitt Rivers Museum and other leading U.K. museums, as well as Carr’s paintings,” Milroy says. “There was an incredible sense of place. [Emily Carr’s] career reset the parameters of what women’s lives could be and the creative freedoms they could embrace.”

When you speak with Milroy, you quickly realize her job is more than just looking at art. It’s about rebalancing narratives, exploring esthetics and both celebrating and exploring stories every piece has to tell. When curating a space, Milroy describes the process as having “a creative intuition and esthetic impulse behind how you bring the objects together and how you make the objects talk to each other in a way that the audience can overhear.” When you look at Milroy’s trajectory, hear her talk about those experiences and her upbringing surrounded by some of art’s greats, it makes sense that it all comes together so seamlessly.

“I do believe people’s homes and their collections are, in a sense, an autobiography”

Even in her own home, the objects she surrounds herself with tell a story. “I do believe people’s homes and their collections are, in a sense, an autobiography,” she says. “People choose the things they’re going to live with, because they tell a story in [a] space about who they are.”

From where she’s sitting, speaking with us, she mentions being able to see a small painting from an artist she mentored, currently studying at Goldsmiths in London (U.K.), as well as a ceramic pot by her daughter, Nellie, who is also busy studying in London. She talks of a painting by Gathie Falk, a gift to her from her mother as a wedding present. “It’s placed in the middle of the kitchen, where most of family life unravels,” she shares. “There’s meaning around not only what objects are in the house, but also where they’re placed.” She continues to say that her living space isn’t curated, as you might expect. “It’s piled with books, guitars, paintings, art my kids made,” she laughs. “It’s not a pristine, modernist house. It’s an arts and crafts pile.”

It’s this connection to people, whether they’re artists, patrons or family, which underpins everything. As she says, “Art brings you closer to how another human being experiences the world. There’s a tremendous intimacy with these strangers that you’ll never meet. A lot of pleasure in art is esthetic, but a lot is rooted in my curiosity about the human experience.”

It’s the moments that turn up in the most unexpected places, however, that have the most impact. On the way to her interview, where she would take the position at the McMichael, Milroy tells us she started talking with her Uber driver. She learned she had moved to Canada from Somalia five years before, escaping an arranged marriage and making a life for herself. When she asked what Milroy was doing in a suit on a Sunday, she responded by telling her she was interviewing to be the chief curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. She shared with Milroy how much she loved the place.

“She told me that, when she first arrived from Somalia, she went there with her children. Everyone made her feel so welcome, and it helped her understand where she’d landed,” Milroy says. “She said, ‘I looked at those paintings and felt that was my introduction to Canada.’ All sorts of people coming from all sorts of places can feel comfortable here, and that’s what it’s all about.”

www.mcmichael.com

@mcmichaelgallery

INTERVIEW BY ESTELLE ZENTIL