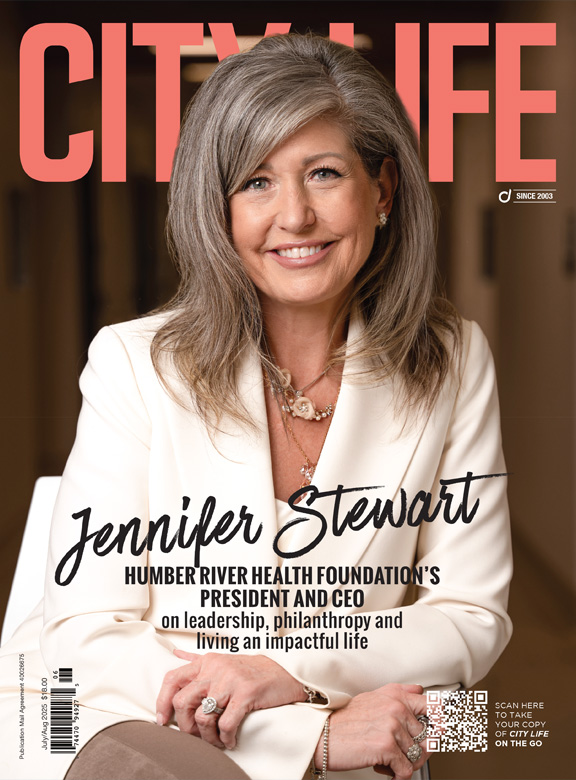

The New Farm: Brent Preston, Storyteller, And Farmer of a New Kind of Farm

Forget factory farms and chasing bigger and bigger yields year after year. The New Farm is all about values and stewardship and keeping your eyes on the prize. It does well by doing good.

Brent Preston doesn’t have the luxury of enjoying a hot or cold beverage and putting his feet up while he talks about his farm. Instead, he’s fielding questions on his cellphone outside. “I’m in the chicken coop right now, doing something that requires no mental attention at all — I’m all yours!” he laughs.

And that’s just fine with Preston. He’s not the kind of guy that likes to stand still. In fact, before he and his wife Gillian Flies bought the farm, he had several careers: a human rights investigator, an aid worker, an election observer and a journalist. He met Gillian in the early ’90s, when they were both working for the same NGO in Malawi, on a project supporting a new government trying to strengthen democratic institutions.

So how did these two crazy kids end up on a farm in Creemore, Ont.? Actually, it’s not as if Brent and Gillian started out looking for a farm. They were living in Toronto with two young kids, and they wanted a weekend property, but couldn’t afford anything. “Somehow we ended up convincing ourselves to buy this farm and live here, without any idea of how we were going to make it work,” he says. They moved to the farm in 2004.

“For Gillian and me, the act of farming has always been a political act, so we’re trying to run a farm business that is sustainable, economically viable, and build community, too,” says Preston. “That outlook of what we are doing grows out of all the other work that we’ve done, whether it was human rights work or international aid.”

It Started With A Few Tomatoes

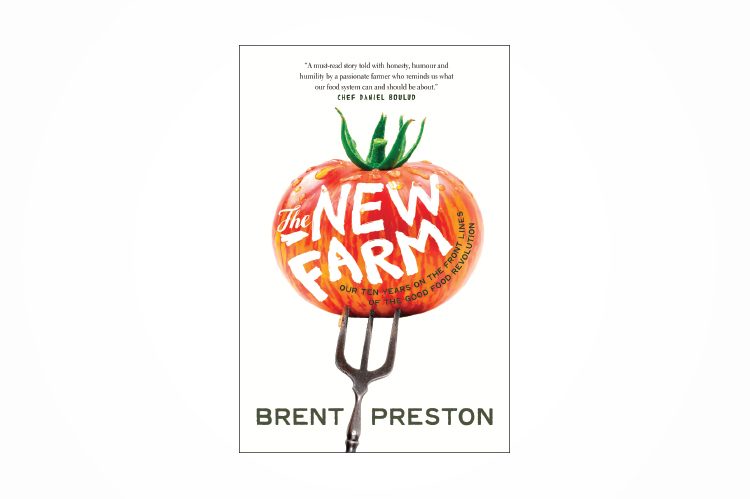

They started out small, with just a vegetable garden for themselves, growing tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers and lettuce. Brent’s family grew a vegetable garden in their Scarborough, Ont., backyard when he was growing up, and Gillian grew up on a farm in Vermont, so they were comfortable with it. Then, they started planting a larger garden and selling produce in the farmers’ market in Creemore. Gradually they began to increase the garden size and the number of outlets and places where they sold their food. “We started selling to restaurants, then to retail stores, and got progressively bigger and more complex as we went, but the whole way along, we were just learning by making a lot of mistakes,” says Preston. “It took a lot of years to get to the scale we’re at now, but it was a process of trial and error.”

For both of them, the most surprising thing when they moved was that there wasn’t a lot of local food available. “We thought that we’d have more access to great organic food, and it turned out we actually had more access to it in the city,” says Preston. So when they started growing it themselves, they realized there was a demand for it.

What Happened To All The Farms?

“The trend toward industrial farming was a result of very deliberate policy decisions made in Canada and the United States saying, basically, that farmers had to get big or get out,” says Preston. As well, the pursuit of free trade deals means farmers in Canada have to compete all over the world when they are growing crops. “A lot of the government regulations around inspections and food safety favour really big operations. We’ve seen virtually all of our small-scale abattoirs and slaughterhouses disappear, along with egg-grading stations. There used to be one in every community; now there are just a handful in very large facilities.”

That’s not all. “We’re addicted to cheap food, and it is a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he says. “With fewer farmers and more consumers, the balance tipped in the market and who the government was going to serve.” So cheap food became the imperative, and people didn’t care how or where it was being produced. Nor did they worry about the impact that cheap food had on the environment or on the welfare of farm workers and farmers, he adds. It’s something that all of us have contributed to.

“For Gillian and me, the act of farming has always been a political act, so we’re trying to run a farm business that is sustainable, economically viable, and build community, too.”

A Farm Whose Time Has Come

Now, 13 years later, the New Farm is a successful business. It’s busy, with distributors picking up produce all the time. “There is tons of demand for our product,” says Preston. This year, they are struggling to keep up because it’s growing all the time. “I think a big part of it is timing. We talk about the good food movement that’s gaining traction with people seeking out good local food — they’re starting to care about how food is produced and understand the impact of food on the climate and the environment,” he says.

Add to this the fact that food culture has changed enormously over the past 10 or 15 years. The term “foodie” wasn’t even commonly bounced around until a few decades ago. “Ten years ago, no one would think of working in a kitchen as a glam or celebrity-worthy occupation, and now we idolize chefs who are celebrities with notoriety,” he adds.

Preston suggests that it’s all of these trends that have made farms such as his more viable, as they all contribute to building more of a market for the kind of food they produce, and more people are willing to pay for attributes that aren’t readily apparent when they’re sitting on a store shelf or on a plate in a restaurant. Don’t be misled, though. “It’s still a super-challenging occupation, and it’s certainly not the easiest way to make money. But farms like ours work now, and it’s because of all these broader changes, because of this whole good food movement that’s more broadly defined.”

When Preston says it’s not the easiest way to make money, he’s not kidding. Any way you look at it, it is hard work. “When we first started, it was a lot more physical labour for us,” he says. “We didn’t have any staff, we didn’t have any people working for us, so we were just out working the fields, planting, weeding, washing and harvesting — all this manual labour, all the time.” Now they have employees doing that, a crew of nine workers, and Brent and Gillian are working all the time keeping everyone organized, loading trucks, making sales calls and working the tractor. “We are just going from 7 o’clock in the morning to 7 o’clock at night, six days a week,” he says.

According to Preston, everyone knows that physical work is necessary on a farm, but it’s the crucial organization of everything that takes a lot of time. “You’re on your toes all the time, figuring out how you’re going to accomplish what you’re going to do, prioritizing and figuring out what tasks are the most immediately important,” says Preston. “I go to bed at night with my head hurting a lot of the time.”

The “Aha!” Moment

For Brent and Gillian, the most important moment in the evolution of the farm came about three or four years ago, when they achieved financial success. “We had paid off most of our debt, so it took about seven years to become profitable,” says Preston. “We had struggled with that for so long, and when that happened, I always thought that there would be this moment of euphoria, but then I realized that it wasn’t the most important thing.”

Preston says they had given up a lot. “We had focused so much on profitability and making it a viable business that we had given up too much to achieve it, physically wearing down our bodies. It took a really big toll on our marriage, and we had a moment at the end of that season when we decided, “Let’s not grow any more [than this].” And that was a good decision, he adds, so they could focus on all of the other things they had let go: family, friends and community, and making their food more accessible to more people. “That has had a profound impact on our business and our ability to continue to do what we are doing,” he adds. “Now we realize that we’re not making more money year after year, but we’re making enough money, and we are diverting our energy toward things that matter even more than money.”

Giving back is important for both of them. Every year, the New Farm hosts a huge fundraiser for Toronto’s the Stop Community Food Centre, a food bank and community kitchen that uses food to help connect communities. “We’ve helped them create connections between low-income urban communities and farmers who are struggling themselves to have that opportunity for their food,” says Preston. “Now our fundraising has grown to the point where we’re also supporting Community Food Centres Canada, trying to spread the model to communities all over Canada, and some of our retailers donate a portion of profit back to the Stop.” Every year, their fundraising efforts generate about $125,000 for the Stop.

All of this paying it forward and good stewardship started out as simply a desire to make good food more accessible to more people, says Preston. “There are so many great people who have gotten involved and so many people who want to be a part of it. It’s really neat, the way these things can grow.”

“Now our fundraising has grown to the point where we’re also supporting Community Food Centres Canada, trying to spread the model to communities all over Canada, and some of our retailers donate a portion of profit back to the Stop.”

The Campsite Rule

At the New Farm, they like to keep it simple. They use technology for communication with clients, figuring out when things need to be planted, and record-keeping, which is especially important in farming. But overall, it’s pretty low-tech. “The only mechanization we use is one small tractor for preparing the ground for planting, and everything else is done by hand. Most of the tools we use have been around in one form or another for at least 100 years.”

And when you’re down in the dirt on your hands and knees a lot, you find artifacts that remind you of the people who farmed the land before you. “We find horseshoes and buckles and bits of harness and things. Our farm was cleared maybe 130 years ago, and out of that time, the majority of that time, this farm has been farmed with horsepower and human power,” says Preston.

Once, he found a stainless-steel lighter that had the monogram of the man who farmed the place in the 1950s. “We find lots of things that remind us that we are stewards of the land, and that this land, which was farmed for centuries before we got it, will continue to be farmed for centuries if we farm it sustainably,” he says. “So we have a responsibility to pass it on in a better state than we found it in.”

Brent and Gillian are not alone. “It’s very satisfying; we’ve always sought to do business with people who share our values, and there are a lot of those kinds of businesses around,” says Preston. There are a lot of people in the world who are doing well by doing good, he adds. “They’re all interested in so much more than just making money — they’re great businesspeople and they’re great entrepreneurs, but I think a big part of that is that they care about a lot of other stuff, too.”

Gifts from The Land

Farming has changed Preston as a human being. “It’s made me a little bit more willing to take things as they come. With farming, there are so many different things that are out of your control — the weather, fluctuations in the market — and so many variables that can go wrong that if you’re trying to control everything and stressing out all the time, you’ll just drive yourself crazy.” It’s made him a little less Type A and a little more willing to sit back and take things as they come.

As for the kids (Foster, 16, and Ella,14), they were so young when they moved to the farm that they don’t remember anything else. But now they’re at the age when a part of them wants to get away from the farm. “They want to be in town with their friends, and they sometimes resent the isolation of being out on the farm; it can be very isolating,” says Preston. “But I think they also have a sense of security on the farm, a sense of home that is really important to them.” The kids help with growing food for the family, but not the commercial operation. “It’s strange because everyone always asks, ‘Do your kids help out on the farm?’ But you wouldn’t ask a lawyer if the kids help out in the law firm,” says Preston.

Neither of the kids has a strong interest in farming now, “because they’ve seen how hard it is!” says Preston. “But even if they were interested, I’d want them to try other things. Go away and experience other places, and then, if they want to come back in the future and work or farm around here, then that’s great.” That’s one of the things that Brent and Gillian love to do with their kids: travel in the wintertime. “Gillian and I met overseas, and we’ve introduced our kids to other places, too,” he adds.

What do they do for fun? “Not enough!” says Preston. “But in the summertime, we love cooking and eating, so we like having friends over here for a big dinner on the front porch — and sometimes we get to steal away once in a while to a friend’s cottage.”

What’s Coming Down the Pipeline

The big change on the farm is that they’ve put in a little event space and a commercial kitchen on the farm. “It’s starting to give us more of an opportunity to make a closer connection to the chefs who make our food and to people who eat our food,” he says. Finished last summer, the kitchen has been put to good use hosting fundraising dinners. “Last week, we had chefs from the Chase and La Colette restaurants come up to do a dinner for 100 people, with proceeds going to SickKids hospital in Toronto,” says Preston. They want to start holding cooking classes that end with everyone eating a big meal together, to showcase the food and the chefs.

With a guy like Preston, one has to wonder what his favourite meal is. “That’s easy,” he says. “In the summertime, we make some fresh pasta — sometimes we make it ourselves and sometimes we buy it — we pick pattypan squash, which are little zucchini, and tomatoes, onions and garlic all out of the garden. It goes straight onto a cookie sheet and into the oven and we roast it, adding a little bit of salt and olive oil. We have those roasted vegetables over pasta, and that’s it.”

Turning The Page

Preston wants to tell everyone the story of the New Farm. And so, he wrote a book (The New Farm, Random House Canada, 2017). Why now? “We’re trying to connect people more closely to this kind of agriculture and get more people out on the farm, to understand that this is viable and that they should support it,” he says. “That’s one of our big focuses moving forward, and the book is part of it as well.”

It’s an honest and funny read detailing Brent and Gillian’s move to the country to start their farm and a lot of the mistakes they made. In the chapter “Castration,” Preston explains why it’s important to castrate male pigs as soon as they’re weaned from their mother, otherwise testosterone can cause “boar taint.” In the chapter “Los Muchachos,” he describes the process of hiring migrant workers from Mexico to work on the farm.

“Our industrial food system is destroying our environment, hijacking our climate, making us fat and sick and unhappy. It’s a huge, overwhelming, complex, multi-faceted problem — but the good news is that there is a huge, complex, multi-faceted movement underway to fix things.” — Brent Preston, The New Farm

The book concludes with a love letter of acknowledgments. “Gillian and I want to tell people the story of the farm and help them understand that this kind of farming is a real option.” The real goal of the book, Preston says, is to encourage other people getting into farming as an occupation to try it and to encourage consumers to care about how their food is produced and seek out the kind of food grown on the New Farm.

“You can spend your whole life reading about how screwed up our whole agricultural system is, but we kind of avoided all that really heavy-handed stuff and said, ‘Let’s just tell our story and try to send the message that this kind of farming really can work.”

Late that fall, at the end of our fifth season of farming, I made the drive to Hanover to see our friend Gerald Poechman, the organic egg farmer, to pick up some feed for the hens we were keeping over the winter. After we had bagged and loaded the feed, we stood around the back of my pickup and talked, like we always did. I told Gerald about the changes we were seeing in the farmers’ market and among our restaurant clients, about how people in all walks of life were starting to make the connection between the food they ate, their own health and the health of the planet. I told him that I thought we were reaching a tipping point, where real change in our food system was possible. And I told him that all these changes had conspired to create the conditions where our little farm, using mostly hand tools and a workforce of committed, idealistic young people, could actually turn a profit. Gerald smiled. “I always knew you could do it,” he said.

Then Gerald told me about the changes he was seeing in his community. He told me about the conventional egg farmer down the road whose laying barn was so highly automated that he could offer his lone worker only twenty hours of work a week. He had recently doubled the size of his operation, to a hundred thousand hens, so he could bring his hired man on full-time. The worker spent most of his day walking the rows of cages, taking out dead birds. Everything else was done by machine. Gerald also told me that many of his conventional neighbours were cutting down the trees and ripping out the fencerows between their fields to accommodate even larger machinery. They were using enormous sprayers with 60-foot booms that could cover an acre of crops with pesticide in a matter of seconds. The landscape was being transformed into massive, unbroken fields, hundreds of acres of perfect, sterile monoculture. Globalized commodity markets and razor-thin margins meant fewer and fewer farmers and bigger and bigger farms. “You’re part of a tiny little segment of agriculture that is moving in the right direction,” Gerald told me. “The rest is hurtling in the opposite direction, as fast as it can.”

“This book has timely and important things to say about food and farming and building a more sustainable future, but it’s also a fantastic story about the new economy, a textbook case of doing good. The New Farm should be required reading for every Canadian entrepreneur.” — Arlene Dickinson, businesswoman, author, co-host of Dragon’s Den

As I drove home through the rolling hills along Grey County Road 4, I turned over Gerald’s words in my head. We had started our farm with a mission to prove that a small farm could be both profitable and sustainable. We had finally succeeded on the profitability side, sort of. Our Season Five sales had grown only modestly over Season Four. We had made enough to cover all our farm expenses and to live for a year, but only because our living expenses were so low. We didn’t spend much money because we were working pretty much all the time. But on the sustainability side, I suddenly realized, we had failed miserably. I truly believed that our farm was ecologically sustainable — our soil was improving each year, we had planted thousands of trees on the farm, our solar panels made us self-sufficient in electricity and we didn’t burn a lot of diesel — but we had been thinking of sustainability far too narrowly. For our farm to be truly sustainable, it had to sustain Gillian and me physically, intellectually and emotionally; it had to provide both a livelihood and a life. Our farm had to protect and enhance not only our air, water, soil and wildlife, but also our family. For our farm to be sustainable, it had to be sustainable for us. And at that point it wasn’t.

There was no way we were going to build a new model of agriculture that required farmers to destroy their bodies, ruin their marriages, forsake their intellectual interests and cut themselves off from their friends and family in order to turn a meagre profit. No one was going to leave the city and follow in our footsteps if they saw the amount of work and stress that we had gone through for the past five years, and we certainly weren’t going to convince any conventional farmers that we had figured out a better way. “The rest of agriculture is hurtling in the opposite direction,” Gerald had said. If we were going to make real change, we needed a viable alternative. And at that moment, despite five years of grinding toil, our farm wasn’t it.

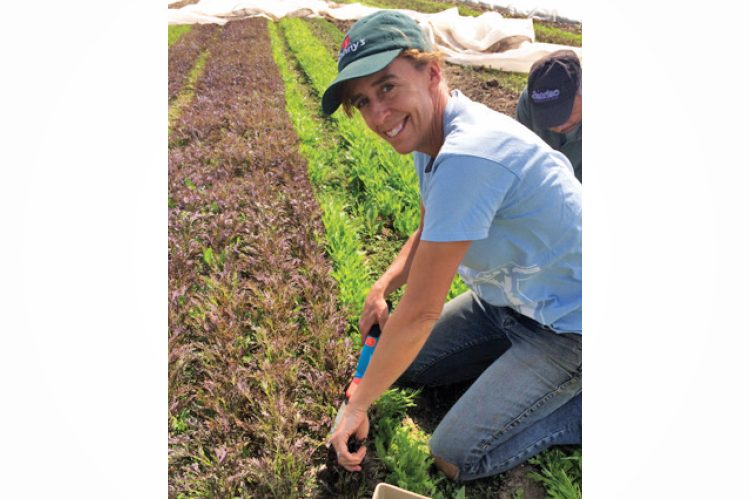

photos courtesy of the new farm

No Comment