The Modern Bard

Shane Koyczan walks onto a stage, his finger nudging the bridge of his eyeglasses up to the radix of his nose. Nervously he rubs his hands together, folding one palm over the other, forming a solitary handshake before an audience awash in a hazy blue light.

He looks out to a gathering of attendees, who despite their successes find resonance in the empowering prose he was invited to disclose at the TED Conference in Long Beach, Calif. “There’s so many of you,” he begins, a thick beard, perhaps his most distinguishable feature, framing his cherubic face. With one hand in his pocket, the other flailing around, the spoken word poet travels back to his childhood, a time when he was asked to abandon his dreams, a place where he was discouraged from being different, a stage on which school bullies tried to get the best of him.

Swinging from humour to sadness, undulating with anger and optimism, Koyczan’s chocolate voice is a pendulum of emotion as he segues into the lyrics of his most stirring poem to date. Peering into his personal bout of being bullied and the psychology of children contending with an issue that can impart profound impacts, he explores one of the universal drawbacks of our early years with an indubitably trenchant effect.

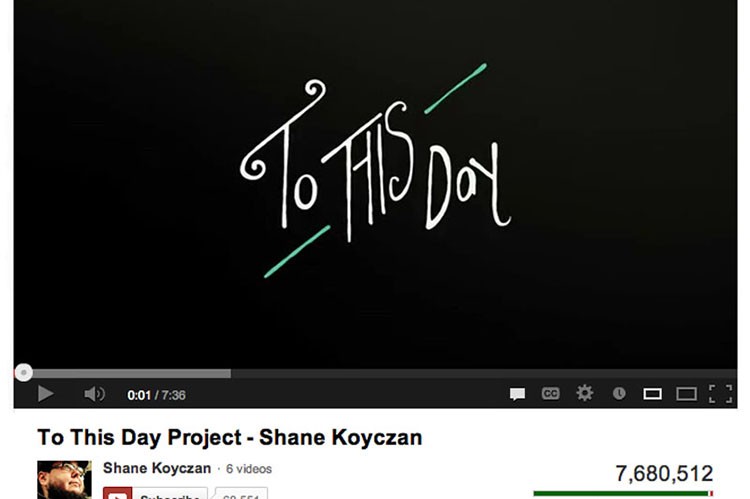

He was the kid called pork chop at school, the kid who stood out for being too different, a definition defined by the cool crew that ruled the battleground of the playground. He wasn’t invited. He didn’t belong. “I grew up being told ‘the world doesn’t need people like you,’” recalls Koyczan, 37. Today, he’s about to board a flight to Vancouver a week before performing in Ottawa. The airport isn’t his most favourite place, but the stamps on his passport indicate a rising Canadian artist whose work is now held in international esteem. The February 19 animated release of “To This Day” has struck a chord amongst a broad spectrum of viewers, receiving close to eight million YouTube hits as of early April.

W. Brett Wilson vividly recalls the first time he saw Koyczan. The former Dragons’ Den star and philanthropist watched the poet perform “We Are More,” capturing the attention of three billion viewers as he sat in awe at the opening ceremonies of the Winter Olympics in 2010. “I saw this kid come on stage wearing a relatively healthy beard and he proceeded to do his rant in support of Canada. I fell in love — call it a bromance — but I fell in love with this artist.” A year later, Wilson was leading Operation Western Front, a charity gala in Vancouver. After a few tries, he finally got a hold of Koyczan and asked him to contribute to the cause. “His first reaction was, ‘I don’t do war.’ Nineteen minutes later he said I understand and let me see if I can fit in. The conversation was, I don’t believe in war either, but I do believe in the people we send to the front line and supporting our troops is different than supporting a war effort. He came around in my way of thinking and ultimately did perform and stole the show again.” A fast friendship ensued, the two collaborating on subsequent events. “I think he’s one of Canada’s true gifts,” says the Canadian entrepreneur.

A supporter of the anti-bullying program Dare to Care, Wilson readily admits to being aggressively picked on as a child by a trio of girls, who tripped him in the hallway and tore his homework into pieces. “I can still remember it very clearly … it was emotionally upsetting at the time.” Naturally, Wilson was moved to tears when he first heard Koyczan describe his childhood, which in some ways mirrored his own. “The first time I heard him do [‘To This Day’] — I’ve listened to it several times before it even came to video — I said, ‘Shane, I’d like to see this turn into a video.’ He agreed and next thing you know he turned it into a video without my support but turned to me and said, ‘Can you help us launch it?’ And I did in a heartbeat.”

Produced by the storytelling studio Giant Ant and featuring the work of 12 animators and an enchanting composition by indie music band Shane Koyczan and the Short Story Long, “To This Day” has everyone talking. “This video is making a difference because it’s allowing kids to engage,” says Wilson,who shares the video with friends and followers on his social media accounts. “All you need is to get people to the table, to talk, and as soon as that begins, the rest all kind of comes nicely together.”

According to PREVNet.ca, a study by Craig and Harel in 2004 found that 15 per cent of girls and 18 per cent of boys have been bullied at least twice over the same period of time. Coupled with the finding that 18 per cent of boys and 12 per cent of girls have bullied others at least twice in previous months, the figures suggest that in a classroom of 35 students, between four and six children are bullying and/or being bullied. “A lot of people have been bullied, and a lot of times name-calling has been one of those things that doesn’t resonate in the realm of physical abuse, but its effects are longer-lasting,” says Koyczan. An act carried out with the intention of hurting someone physically or psychologically, bullying includes verbal and physical abuse, and cyberbullying, a vehicle of violence more prevalent than face-to-face interactions. “I would hate to grow up in today’s society,” says Koyczan, whose childhood predated the social media era. “It’s difficult because there is no haven anymore. The Internet really allows the bullies to enter the home and all you can do is switch off.”

Born in Yellowknife, Koyczan describes the stem of his torment as a series of events that quickly compounded, the mounting taunts at school becoming unbearable for him. “Being raised by my grandparents, a lot of kids began questioning, ‘Why are your grandparents taking care of you?’ And then that became, ‘Your parents don’t want you.’ After that, it was kind of easy for them to gang up and invent new things that they could say.” It was a fact of his life that the children at school sunk their teeth into like fresh meat, tearing at him until there was nothing left. His grandmother, Loretta Mozart, never left his side. “She knew how hard it was and it was really like she was trying to get me through the next day. I’d come home and there would be new stories of torment and despair. She’d say, ‘All right, let’s hear them.’ That was enough to make it bearable, to make me get up and trudge to school.”

Dr. David A. Wolfe, director of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Centre for Prevention Science in London, Ont., describes bullying as a repetitive act, its persistence distinguishing it from other forms of aggression. Although bullying can change from elementary school to high school, he explains, the stakes become higher when children seek to overpower each other. Losing that power play can increase one’s susceptibility to the act. “Let’s say one boy doesn’t have any power over another boy. They’re both on the same baseball team, the same age, the same height. They don’t tend to bully each other — they bully someone who is different from them and seems weaker. The weakness is in the eyes of the bully,” says Wolfe, who is also a program director of The Fourth R, a school-based program that encourages healthy relationships in young people.

For the past 10 years, Koyczan has immersed himself in spoken word poetry, a centuries-old art form that reached popularity in the 1960s. As a kid he sought refuge in an artistic realm — insulating the crevices of his mind with material that befriended his creativity and imagination. It was a reprieve from the torture, a secret hiding place from the bully and his cast of idle bystanders. “There wasn’t a physical place I went to, it was more like a medium. Comics, literature and film — none — of it was there to judge me. That was my great escape,” says Koyczan, who later enrolled in the creative writing program at the now defunct Okanagan University College. He began with short stories and chapters for novels before discovering poetry was the quickest route to emotionally express his feelings. In 2000, at the National Poetry Slam in Rhode Island, he became the first Canadian to win the Individual Championship title. In 2009, Koyczan and the Short Story Long received Best New Artist at the British Columbia Interior Music Awards. He has since written three books: Visiting Hours, Stickboy and Our Deathbeds Will Be Thirsty.

At the age of 14, a wave of relief swept through Koyczan. His grandparents had decided to move from Yellowknife to Penticton, British Columbia, in search of a warmer climate. A prepubescent Koyczan jumped at the opportunity to lead a new life, one where no one would know of his past — one that would allow him to enjoy being a kid. But on the first day of school, his hope of a fresh start began to unravel. For weeks he suffered in fear and sadness, until the day everything changed. He became someone he loathed: a bully. “I’d been in enough physical fights at that point that I knew what I was doing. I knew how to hurt someone,” says Koyczan, who describes that period as one of the lowest moments of his life. “It was devastating to see the look on my grandmother’s face.”

Wolfe explains that while it’s not common, it’s not that uncommon for victims to become bullies. “Some kids that are victimized realize that if they simply change their approach a bit, they can be the ones delivering the pain. They change how they look or they change whom they associate with. They steal something that someone wants so that they’re now accepted as a friend. They’ve shifted their politics,” says the psychologist and professor, who specializes in issues that affect children and youth. “I think it was a defence mechanism,” says Koyczan. “When students smell blood in the water you have to prepare for the swarm. It’s that mentality.” He has since received an email of atonement from one of his greatest tormentors at school — the power of apology helping him heal some of his battlefield scars. He’s paid the gesture forward, and while some accepted his apology, he understands why others haven’t. He pauses, clearly affected by the repercussions of becoming a bully, to describe the person he is today. “I don’t know. I guess I don’t really think about it. For me a lot of it is just penance. I’m trying to make my life better, and a lot of it is this is me forgiving myself.”

Measuring bullying and victimization, a recent WHO survey suggests that the prevalence of bullying in Canada has remained relatively stable over the years, but a dismal ranking on the world stage draws a different picture. When compared to other nations, Canada is lagging behind in the prevention of bullying. Koyczan’s recent contribution to the Dalai Lama Center for Peace and Education speaks to the need and responsibility of parents and schools to take a more hands-on approach when it comes to equipping children with the tools they need to navigate the world. Koyczan points to qualities such as compassion, acceptance and tolerance to win the bully battle in the Center’s Educate the Heart initiative. “If we want our children to grow into socially and emotionally capable young people, we must ask for a balanced education that puts importance on educating both the mind and the heart.”

Reminded of his long-reaching efforts, with millions finding comfort in his contributions, he reflects on his journey thus far. “It was amazing to be in a room full of people who maintained who they were despite what they’ve been through,” says Koyczan, whose conversation was voted a tall second in the most popular contributions at TED Talks in 2013. While he’s floored by all the fanfare, Koyczan explains that his viral hit was born with the sole intention to help people, to underpin the downfalls of the dejected and downcast with the message that every cloud has a silver lining. Plucked from the scrolling comment section of the “To This Day” video, a short sentence marks the remarkable impact and extraordinary feats of a man once told he didn’t belong: “The world needs more people like this.”

www.shanekoyczan.com

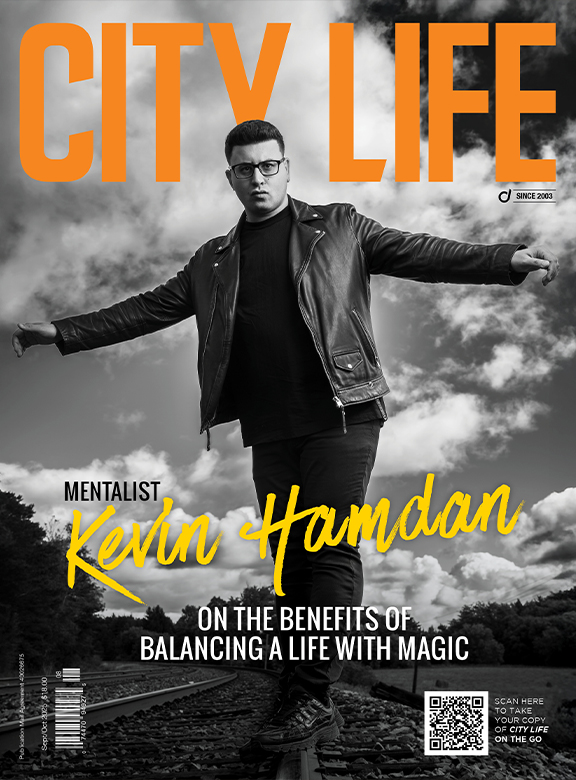

No Comment