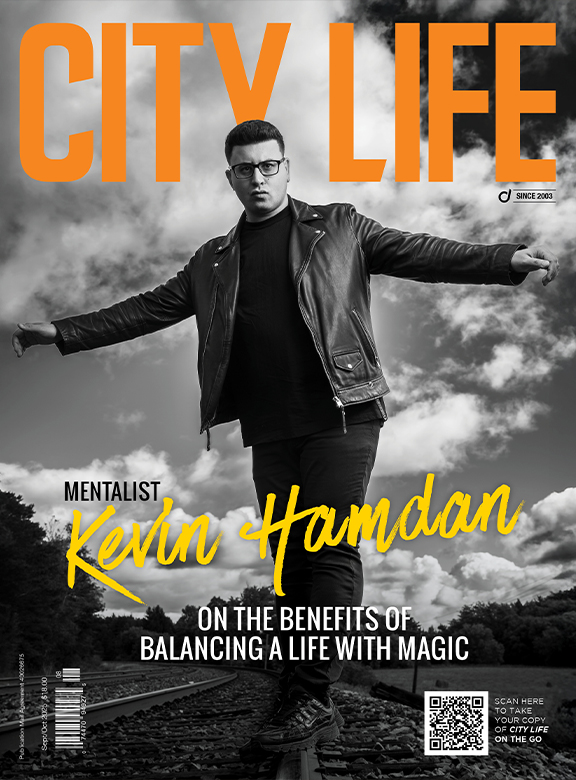

Losing Patience

Anthony Socci has spent the last three years waiting for a new kidney. How one man copes and how we can help

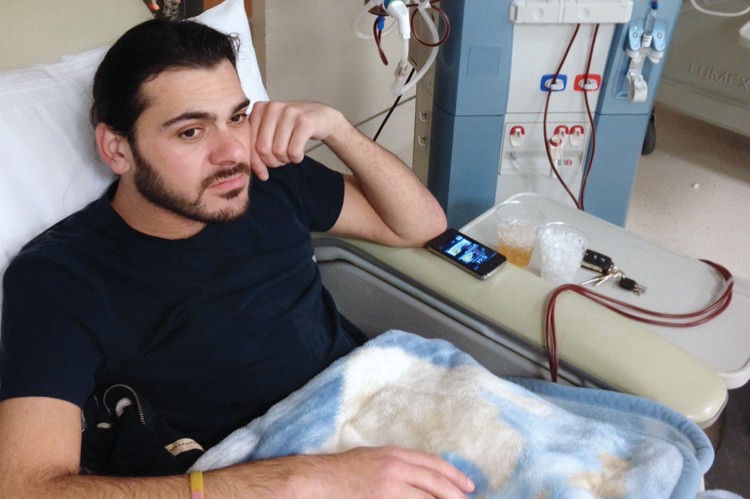

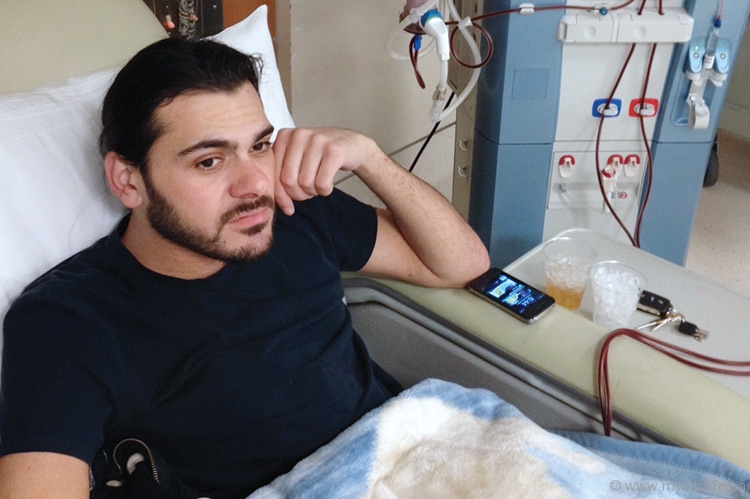

What’s four hours to you? It’s half a work day; half a full night’s sleep. Four hours can be a movie marathon or a running marathon, a visit to the beach or a drive to the cottage. But to 28-year-old Anthony Socci, four hours is the amount of time he has spent in dialysis five days a week since his kidney failure three years ago. But what’s worse is that his waiting doesn’t end there. Socci, a Richmond Hill native, was born with the rare Fabry’s disease — a genetically inherited condition that results from a buildup of a certain type of fat called globotriaosylceramide. Socci spent his childhood suffering with excruciating pain in his hands and feet, blocking him from the soccer field and social scene.

“Things just got a thousand times worse after my kidney failure,” Socci explains. And it wasn’t only the physical pain that multiplied. The emotional toll became staggering as his daily dialysis began, stripping him of his time and energy, and as the strenuous search for a kidney donor got underway. “It got to the point where he was going through all these excruciating treatments for the sake of staying alive, but it was robbing him from actually living his life,” says Anna Maria Socci, Anthony’s aunt and one of his most cherished caregivers. But what Socci claims hurts him the most is the ticking of the clock. In the beginning, there was the nail-biting span of time while he waited for his lifesaver to step up. But even though an anonymous donor finally offered his kidney after the Step By Step Organ Transplant Association hosted a fundraising event for Socci in

January of 2012, the waiting period between the donor’s offer and the actual transplant is still taking an unbearably long time.

Now, after watching the clock for three years, Socci has grown tired of waiting.

“We need two things,” he says. “The first is awareness. We need more people donating their organs. We need them to know why it’s important and how they can go about donating. The second is a shorter amount of time between when a donor steps up and when the actual surgery takes place.”But according to Dr. Gary Levy, director of the Multi-Organ Transplant Program at the University Health Network, these goals are one and the same. “There are many reasons why the process could be protracted,” Dr. Levy says. “It all depends on the testing results, and on the candidate’s availability to be tested. Also, many of the candidates decide along the way that it’s too risky and opt out.” These setbacks have cut one’s chances of successfully becoming a donor down to one in six, making the selection process a long and tedious one. If more people were stepping up to become a live organ donor, Dr. Levy says, those chances would increase — in turn speeding up the waiting time. Patients like Socci aren’t the only ones advocating for more donors to step up. Past donors like Clairmont Humphrey, who donated a piece of his liver to a 14-month-old baby girl in 2008, are rallying for other healthy candidates to join them in saving lives. “The waiting list in Ontario is too long, and folks are dying every day. They don’t have to die,” says Humphrey. “We’ve been told time and time again that it’s better to give than to receive, and becoming a living donor is the epitome of that calling.” It’s a calling that many would label as terrifying, but Socci doesn’t underestimate people’s bravery and goodwill. Even though still waiting for the operation, he appreciates what it means for a donor to anonymously offer him a kidney. “It feels amazing, seeing the goodness in people. Knowing that that kind of goodness actually exists in humanity is humbling and refreshing.”

To register as a live organ donor and discover if you’re able to save someone’s life, speak with the organ and tissue transplant team at your local hospital.

No Comment