Is a path toward healing possible?

It is time for all Canadians to gather together in a spirit of tolerance and action. But, to open our hearts to healing and reconciliation, we must first take the time to understand this dark period in Canadian history.

It is almost impossible to envision. But, the discovery of the remains of 215 children on the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in Kamloops, B.C., on May 27 of this year, demands that we do so.

Add to that the further discovery of 751 unmarked graves (most of which are thought to be the graves of Indigenous children) at the Marieval Indian Residential School in the small Cowessess First Nation community in southeastern Saskatchewan on June 24th, 2021, and the demand becomes a resounding cry for priority exploration of all residential school sites, and a deep unflinching spotlight on humanity, honesty and apologies. (Criminally, in a 1960s dispute between a priest and the Cowessess chief at the time, many of the grave markers at the Marieval School were bulldozed to the ground by the priest.)

Added to these heartbreaking, psyche-shattering discoveries, is the certainty that more graves will be found on some of the land sites of the 130 residential schools that operated across Canada, including the Red Deer Industrial School in Red Deer, Alberta; the Muscowequan Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan; the Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford, Ont.; and the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School, north of Halifax, Nova Scotia, to name but a few.

And so, imagine yourself as an Indigenous mother or father, aunt or uncle of a young child or of many children. You are sitting around the kitchen table as a family or standing at the stove, stirring homemade soup for dinner as someone sets down the dinner amid loud bouts of laughter. Quite possibly, you are working out back of the house, piling wood or digging a vegetable garden for the family’s sustenance, when suddenly you hear an insistent pounding at the front door, a fist that is hand-wrapped around terrifying news.

In fact, for Aboriginal Canadians with young children, one of the things they feared and dreaded the most in the broad span of time between the 1870s and 1996 was that hard authoritative bang on the door announcing the presence of an RCMP officer and an Indian government agent, whose job it was to remove the children of these Indigenous families from their homes and take them to one of 130 residential schools across the country.

“I ask you to imagine what you would feel like if your children were literally ripped from your arms and forced into a school where they experienced every type of abuse: sexual, physical, mental and emotional. You are told you are stupid because you couldn’t speak their language (English) and that you were dirty because your skin was brown,” says Patricia Nolie, of Alert Bay, B.C. Her grandfather was a residential school Survivor.

Often, these children were placed hours from their homes, whisked away on boats and other means of transportation, while their parents keened and wept in their own doorways, terrified of the RCMP and what it might do to the rest of their family if they did not give up their offspring.

Since the announcement of the discovery of this unmarked mass grave at the largest school in the Indian Affairs residential school system, Kamloops Indian Residential School, which was run by the Roman Catholic order of nuns The Oblate Sisters of the Immaculate Mary, Canada, Canadians of all cultures and races have been alternately up in arms and in disbelief and at the same time devastated, sickened and united in their horror and grief for these abused and stolen children. Of equal pathos is the fact that, officially, only 54 deaths were recorded at Kamloops Indian Residential School through the years, which is representative of a mere 25 per cent of the 215 hidden remains that were found through ground-penetrating radar on that grim May day.

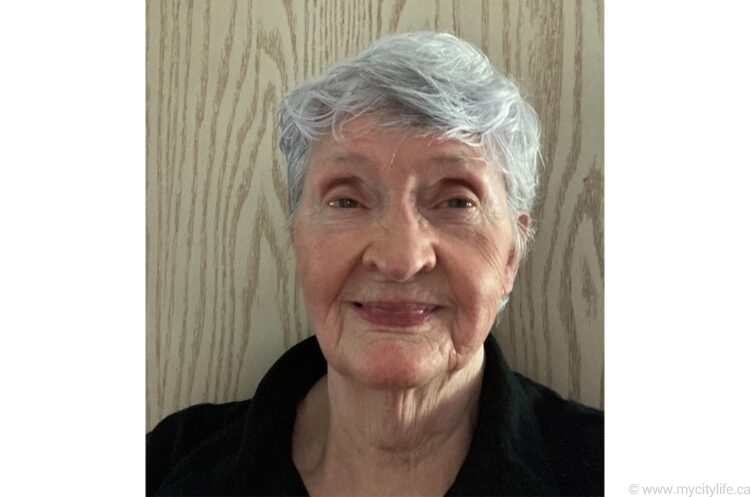

“I have been crying for days — ever since I heard the news about those children. Every time I turn on the TV, and they are talking about it, I just break down and I cry and I cry,” says Susie Alfred, 82, of Witset, B.C., who is a day school Survivor.

How did this happen in a country known for its gentle and passive spirit, a welcoming country known for its tolerance and acceptance of diverse nations and their cultures?

For those not familiar with the residential school project, it is important to understand the reasons why the removing of Indigenous children from their parents happened in the first place and then why and how a school system that was run in tandem with the Canadian government and members of five high-profile churches — Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian and the United Church of Canada — could execute so many untold acts of abuse on a mental, physical and sexual basis, all while servicing their respective gods. (A total of 60 per cent of the residential schools were run by the Catholic Church.)

It is believed that close to 150,000 First Nations, M tis and Inuit children were taken to residential schools between the 1870s and 1996, when the doors were finally closed on this shameful travesty.

“This is such a dark time in our history,” says Marilyn Brown, a former nun who lives in Orillia, Ont., and no longer practises her faith. Like so many Canadians, she is horrified by the recent news. “In fact, at one time there was a saying, ‘Take the Indian out of the child,’ which was one of the end goals of the residential schools. There was little — if any — respect for the Indigenous culture. In fact, they were called ‘savages.’”

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, “residential schools were created by Christian churches and the Canadian government as an attempt to both educate and convert Indigenous youth and to assimilate them into Canadian society.”

It appears that the educational curriculum for these Indigenous children was violently clear: no child was to speak their language or otherwise engage in any fraternizing with their siblings, who were commonly housed in the same schools. No child was to flourish under the kindness of the clergy who ran the schools, for, while there must have been some good and kind clergy and workers within the system, there were many who violated their religious vows. Too, children who were the targets of sexual abuse were ashamed to speak of the frightening and confusing things that happened to so many of them on a nightly basis.

Alfred is both a day school Survivor and a descendant: her mother, Margaret Williams, along with some of her siblings, had been taken by the RCMP and an Indian agent to a residential school hours away from their home. “My grandparents were afraid that the RCMP would put them in jail, so they let them take their kids away,” Alfred says. “My mother told me that when they spoke their language, they were strapped with a thick, heavy rubber strap about half an inch thick and two feet long. My mother also told me about a time when her two brothers tried to sneak home by walking down along the CN Railway tracks. They got caught and were taken back to the school, where they were worked over before being put in the basement with no window — they were just left there. My mother used to cry about it a lot.”

Children running away from the cruelty, fear and abuse is not a singular event. Famously, the late Gord Downie, former lead singer for the Tragically Hip, drew the public’s attention to the tragic death of 12-year-old boy Chanie (Charlie) Wenjack, an Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) First Nations child who ran away from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ont., in 1966, with his 10-song album, Secret Path, in 2016. Wenjack died of hunger and exposure as he tried to walk the 600 kilometres back home to his family on the Marten Falls Reserve. Alfred’s memories of her own time at residential school all those decades ago came back in a painful rush when she heard the news of the recent finding of the 215 children’s remains.

When Alfred was in Grade 5 at the day school, she was abused by a priest.

“There was a wood stove in the basement, and the Sisters made us go down there to put wood in the stove. A priest was hiding behind the stove, and he grabbed me and shoved me in a corner. He sexually abused me, and I thought it was my fault. I never told the Sisters or my mom and dad. I was traumatized so badly all of my life, but I never told anyone. When you’re young, you think it’s your fault — that’s how I thought.”

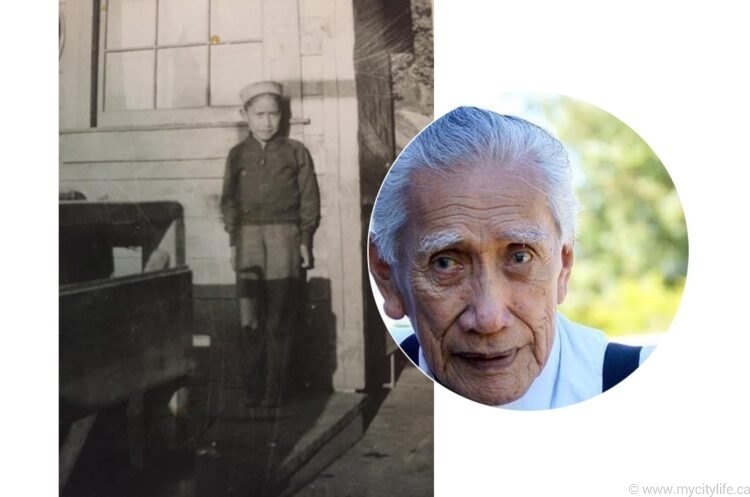

Patricia Nolie is the granddaughter of Alfred James Nolie (Jack), who, along with Patricia’s grandmother, raised her. Patricia’s mother was in the throes of addiction and not able to look after her children.

Jack was four years old when he was first brought to St. Michael’s Residential School (run by the Anglican Church), in Alert Bay, B.C.

“When settlements were being offered to Survivors of Indian residential schools, I sat with my grandpa through that process to help him understand what the government was offering,” Patricia says, her voice a chasm of emotion.

In fact, our conversation is interspersed, often halted, as the tears of Patricia’s ancestors flowed.

“Throughout the years my grandfather was at the school, he watched his eight siblings come through — he tried his best to look after them,” Patricia says. “My grandfather would get whipped for speaking his Kwak̓wala language, but he didn’t know how to speak English. He told me, ‘I never knew what hate was until I was in that school.’”

Some of the heartbreaking experiences that Jack shared with his granddaughter include the fact that the children’s breakfasts — often oats — would be interspersed with maggots. Children who did not eat their breakfasts were often served it again at lunch. Bathrooms were padlocked at night, and children would wet their beds, which resulted in harsh punishment. In order to mitigate this, Jack showed the younger boys how to pee out the window, but he got caught. In retribution, Jack had to scrub the boys’ bathroom floor with a toothbrush and then use the same toothbrush to brush his teeth.

Often, older boys would situate themselves by their dormitory door, so that the younger ones wouldn’t be taken away at night by the priests, for sexual encounters.

One of Jack’s punishments in particular scarred him physically for the rest of his life.

“When my grandpa was 10 years old, he was starving, so he went to the garden at the back of the school and stole a turnip. He got caught and was dragged to the chicken coop, tied up and beaten with a twoby- four. He was in the infirmary for six months and couldn’t walk. It wasn’t until he was in his 40s and went to a back doctor, because he was in so much pain, that my grandpa found out that his back had been broken all those years ago. This is only one account of his time in that school. After I heard his stories, I applied for trauma counselling, because it was too heavy for me to carry. I started drinking more and even attempted suicide,” Patricia recounts.

So, where do we as Canadians — mothers, fathers, clergy, government representatives and Indigenous communities — go from here?

First, it is worth looking at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), which was established in 2008 for the purpose of documenting the lasting impacts of the Canadian Indian residential schools on Indigenous students (which has proven to have had a generational and troubling impingement) and their families. It was estimated that at least 6,000 children were reported to have died at the schools, which is believed to be a significantly low accounting. The commission, which provided residential school Survivors with an opportunity to share their stories, was centred on five pillars: Child Welfare; Education; Language and Culture; Health; and Justice.

The involuntary sending of Indigenous children to these residential schools with the intent of rooting out and destroying the Indigenous language and culture prompted a shocking and devastating statement by the TRC chair, Justice Murray Sinclair, in a May 29, 2015, CBC interview with John Paul Tasker: “I think as commissioners we have concluded that cultural genocide is probably the best description of what went on here.” (On June 9, 2021, Canada’s federal NDP Party called on Ottawa to recognize residential schools as genocide.)

Of the 94 recommendations made by the TRC in its report, as of 2020, only eight Calls to Action have been completed. Recommendations 71 through 76 in the report, included under the Missing Children and Burial Information, speak specifically to several accountabilities at the chief coroners’ and provincial vital statistics levels. Records on the deaths of Aboriginal children in the care of residential school authorities, federal government allocation of sufficient resources to develop and maintain the National Residential School Student Death Register, a call for the federal government to work with all parties involved to establish and maintain the National Residential School Student Death Register and a call on all levels of government, churches, Aboriginal communities, residential school Survivors and current landowners to implement strategies for the ongoing documentation and commemoration of residential school cemeteries and sites where residential children were buried appear to have a much better chance of being actualized since the discovery of the children’s remains on the Kamloops residential school site. (Source: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” 2015. https://nctr.ca/records/ reports/.)

Rennie Nahanee, who is a deacon with the Catholic Archdiocese of Vancouver, offers an insightful perspective on what happened and what actions can be taken toward healing.

“The first thing we have to understand is, who is doing the reconciling? Do the Indigenous people have to reconcile with the church, or does the church have to reconcile with the Indigenous people?” Nahanee posits. “The people who ran these schools — clergy and lay people — appear to have worked under the auspices of an angry Old Testament God, which they brought with them to teach the kids in the school. Those children never got to know the New Testament Jesus, who is a loving being.”

Interestingly, Nahanee, who is a member of the Squamish Nation, says his faith remains strong. “Maybe God put me here to learn the workings of the church on the one hand and to be a gateway to Indigenous culture on the other,” he says. “Because the church took away our language and culture, I’m trying to organize a right of liturgy for Indigenous people, where we would bring our language, our culture and our spirituality into the Sunday mass and funeral services.”

On June 2, 2021, the Archdiocese of Vancouver released an “Expression of Commitment,” apologizing profoundly to residential school Survivors and their families. The archdiocese promised to be fully transparent with its archives and records, and offered mental health support and counselling for family members and others whose “loved ones may be buried on the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.”

“There are moments in the life of a country that determines how people go forward and, to me, this is one of those moments for Canada,” says Chief R. Stacey Laforme, the elected Chief of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation (MNCFN). “This is a moment that can make us stronger and better, so that something good can come of this.”

RECONCILIATION

I sit here crying

I don’t know why

I didn’t know the children

I didn’t know the parents

But I knew their spirit

I knew their love

I know their loss

I know their potential

And I am overwhelmed

By the pain and the hurt

The pain of the families and friends

The pain of an entire people

Unable to protect them, to help them

To comfort them, to love them

I did not know them

But the pain is so real, so personal

I feel it in my core, my heart, my spirit

I sit here crying and I am not

ashamed

I will cry for them, and the many

others like them

I will cry for you, I will cry for me

I’ll cry for the what could have been

Then I will calm myself, smudge

myself, offer prayers

And know they are no longer in pain

No longer do they hurt, they are at

peace

In time I will tell their story, I will

educate society

So their memory is not lost to this

world

And when I am asked

what does reconciliation mean to me

I will say I want their lives back

I want them to live, to soar

I want to hear their laughter

See their smiles

Give me that

And I’ll grant you reconciliation

R. Stacey Laforme

As far as the recommendations from the TRC are concerned, Chief Laforme says it is not about words or recommendations; it is about strategies and action.

“Don’t tell me you’re going to do it; show me a strategy, with accountability markers attached,” he says. “There are good intentions, but without a strategy to go along with it, those ideas and visions can sit for a long time without being actualized. Building relationships and reconnecting the people of these lands are key. Let’s join together and figure out where we go next and how we can move this country forward in a good way, to not only better the lives of the Indigenous people, but [also]the lives of all marginalized people who suffer in the Children’s Aid system, the jail system, the policing system and through racism in general. There are so many people suffering; don’t separate the Native people.”

As Canadians show their concern over this recent tragic event, many are wearing a splash of orange, the colour chosen to recognize the spirit of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The actual day of observance is Sept. 30, the day Indigenous children were taken from their families to residential schools.

“It hasn’t been easy hearing this news, because my grandfather knew — we knew — that there were children buried on residential school sites. We have never been heard, never been understood — we have just been told to get over it. It took this proof — the finding of these 215 children’s remains — to prove that there was genocide. People tell us it was a long time ago. But it is a part of us. I am still living it,” Patricia says. “We are strong, but we are tired of fighting a system that was built to break us. I have cried so many times in the last few days thinking of those children and how scared they were in those last moments of their lives, their families and home far away from them.”

The remains of an additional 182 children were found on June 30th near the former St. Eugene’s Mission School for Indigenous children in the Aqam community.

On that same day, June 30, in recognition of the sorrow, shock and heartfelt pain that Canadians right across the country have been feeling about the abuse inflicted on the residential school children and their eventual deaths, A Day to Listen, a partnership between the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) was held. On that day, Indigenous people from all walks of life, including elders, residential Survivors, educators and Indigenous leaders shared their stories with listeners. Over 500 radio stations across Canada participated in this poignant 12-hour day of listening, whose mission was to initiate and foster real and measurable change, so that as we try to heal as a country, we have the education and power to create the kinds of forward actions and solutions that will result in a resonant and tolerant future for all Canadian citizens.

If you are suffering pain or distress as the result of a residential school system experience — either yourself or a family member or a friend — the Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.

Additional resources include: Tsow-Tun Le Lum Society: 1-888-403-3123 (seven days a week); and KUU-US Crisis Line: 1-800-588-8717 (24-7).