Botannica Tirannica: Honouring Nature’s Culturally Indigenous Roots

The renaming of plants during colonial times erased many native and cultural practices. The mission behind the Botannica Tirannica exhibitions is to bring awareness to these injustices and advocate for the kinds of changes that honour our collective past.

How important is a name, and would you still be the same person if you were called something else? Shakespeare had Juliet of Romeo and Juliet fame say, “That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet,” but in truth, a name is an important and personal identifier, and many anxious and excited expectant parents spend hours — if not days — making lists of possible names to choose just the right one to fit their baby’s heritage, culture and personality, often honouring their new addition by naming him or her after a beloved family member or friend.

These days there is a growing awareness of the significance of names, how we identify the everyday things in our lives and what we call them. That is the point made by Toronto’s Koffler Arts’ new exhibition, Botannica Tirannica, a Latin phrase that pointedly references the tyrannies of botanical labelling that occurred during colonization.

The premier exhibition, created by award-winning Brazilian author, professor and artist Giselle Beiguelman, was first shown at the Museu Judaico de São Paulo in 2022.

“Botannica Tirannica is an arts-based research project that investigates the relationship between hegemonic science, classical botany and the colonialist imagination that is historically present in the domination of nature,” Beiguelman says. “Its focus is on the scientific and popular nomenclatures of plants and how they reveal the pervasiveness and naturalization of prejudice and discrimination in our daily lives.”

Beiguelman’s interest in the historical taxonomy or renaming of plants during colonial times was initially piqued by a gift of a Tradescantia zebrina seedling, a plant commonly known as “Wandering Jew.” Considered to be a weed, it was said to have the capacity to infiltrate and spread throughout gardens, parks and public spaces.

“The plant’s name refers to the legend of the Wandering Jew, which originated in 13th-century Europe. Folklore stated that Ahasuerus, the Persian king of the Book of Esther, cursed Jesus on his way to Calvary and was condemned to roam the earth eternally,” Beiguelman says. “Despite its origins, the legend has been used in anti-Semitic narratives, notably by Nazi Germany.”

This derogatory term embedded in a plant’s name inspired Beiguelman’s quest to explore how common botanical names both mirror and perpetuate societal prejudices against racial, cultural, gender and social groups.

“For this exhibition, which brings together natural and artificial gardens, I worked with Artificial Intelligence to create new hybrid beings, whose datasets were composed only of plants with prejudicial names, suggesting the possibility of a world without borders based on prejudice. They are positioned as resistant and resilient life forms in a post- natural, decolonized garden,” Beiguelman says. “These plants were named by the colonizers, who conquered the lands and erased original forms of knowledge. Also, they reflect negative connotations to Black people, women, Sinti (Romani people of Central and Eastern Europe), Rome and Kale and Jewish peoples, revealing how colonialism built its imagination through the invention of the other’ in order to legitimate its supposed rights to subordinate and subjugate.”

Plant names identified by Beiguelman as being discriminatory against specific races or cultures are catalogued under different groupings, including those referencing women, Indigenous people, Blacks and the LBGTQ community.

“People tend to look at plants as ornaments or food but never really consider that plants are part of our culture and nature; there is no division.”

— Giselle Beiguelman

“About 1,200 plants have scientific names like Virginia, vaginatum and Virginian, reflecting the misogynist strategy of sexualizing the female body,” Beiguelman says. “Four hundred plants still use the K-word derogatory to Black people and 100 are explicitly anti-Semitic. These are examples of explicit racism in nomenclature.”

Other plants whose names have derogatory references include the Virginia spring beauty and Virginia bird cherry, both seen as misogynist and racist for equating delicacy, purity and virginity with white women. The nipple fruit erotically references the female body, while the black-eyed Susan embodies a sexist association with domestic violence.

Indian pipe and squaw weed, which uses a racist term for Indigenous woman, are also considered offensive.

“The first thing the colonial renaming of plants did was to erase the native knowledge and cultural practices that were around before the Europeans came to the Americas,” Beiguelman says.

In fact, she says that the sugar maple, which was used for medicine in pre- Contact times, has “had its ancestral meanings erased by colonialism, turning it into a national symbol of the conquering peoples.”

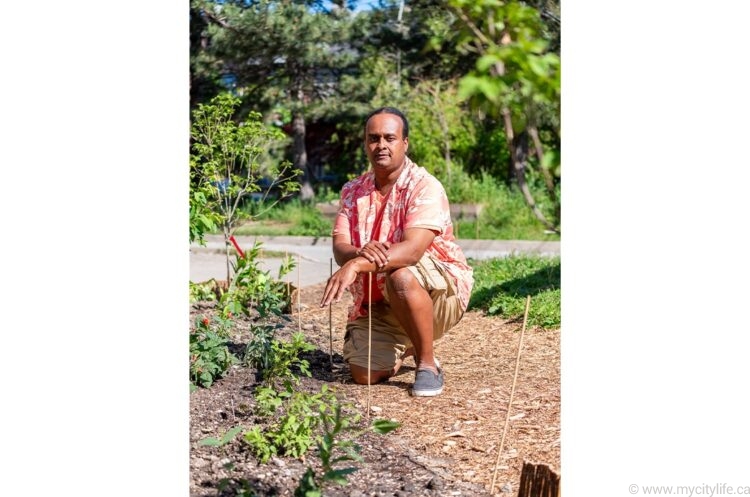

The Toronto version of Botannica Tirannica, at the Youngplace building at 180 Shaw St., runs to October 20, 2024. Canadians Dr. Jonathan Ferrier, a Mississauga Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) scientist and biology professor at Dalhousie University, and Isaac Crosby, a Black/Ojibwe knowledge keeper and agriculture expert, had some input about our country’s Indigenous plants.

“I got all of my farming education and herbal knowledge from my grandparents and great-grandparents, which is how I became a knowledge keeper,” says Crosby, whose passion for gardening and sharing his expertise concerning Indigenous food systems dates back to his Black/Indigenous pre-Confederation band roots. “I have been gardening in Toronto for 20 years and currently teach Indigenous agriculture at the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus, under Professor Dani Kwan-Lafond in the Sociology Department. Students who attend my courses want to learn about Indigenous agriculture, how to cultivate the different seeds and harvest them, as well as learn how to prepare these types of foods properly. My classes are a mix of young people, adults and seniors, an intergenerational mix of people who are interested in learning about plants across many cultures.”

The reintroduction of traditional foods that have been lost to us is a key component of Crosby’s teachings, and in his Indigenous Garden at the university he includes plants that have medicinal as well as other valuable properties. Such as the groundnut plant, which is good for diabetes and for controlling land erosion. The fruit of the tropical pawpaw tree, Asimina triloba, which has taste notes reminiscent of pineapple, mango and citrus and is traditionally used to make delicious puddings, pies and cakes, should also be prized for its other qualities, he says.

“The pawpaw fruit is good for male reproductive organs and also has uses as an anti-cancer, anti-fungal agent,” says Crosby, who hopes to open a dialogue with visitors who visit the Garden of Resilience at Toronto’s Botannica Tirannica exhibit.

The garden itself is 600 square feet (about 56 square metres) and contains a variety of plants.

“The intention of the garden is to tell the story of the colonization of plants and how their names were changed,” Crosby says. “I would like visitors, as they start along the path, to view the Indigenous plants with the names given to them by the people who originally lived here, including their nutritional and food values. But as the pathway curves, symbolically illustrating that colonization did not happen in a straight line, visitors will see fewer and fewer of the native plants and more plants with either their current or Latin names. They will see plants whose medicinal value is gone, with their worth now being measured in beauty or capital.”

Beiguelman and Crosby agree that it is time to dismantle the patriarchy and take a hard look at the current names of plants and change them where needed. “People tend to look at plants as ornaments or food but never really consider that plants are part of our culture and nature; there is no division,” Beiguelman says. As for Crosby, his hope is that a lot of young people will attend the exhibit because he believes that they are today’s change advocates. “We need to get the discourse started as to why some plants have names that cast aspersions on particular races, lifestyles, cultures and the female demographic. One day, one step at a time.”