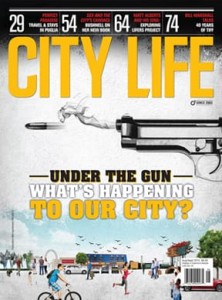

Ask For Angela: Creating An Alternative Way To Get Help

Information tools and action-based steps are critical as we address the shame and fear attached to gender-based violence.

The numbers are both alarming and tragic. She was someone’s mother, daughter, sister, aunt, or best friend. Or maybe she was the neighbour you used to wave to on warm summer afternoons.

The Ontario Association of Interval & Transition Houses website reports that “over the last three years Ontario has seen on average one or more femicides per week. In 2021–2022, 52 femicides were confirmed in the province. This number rose to 62 the following year, a statistic that was repeated in 2023–2024.”

And so “Ask for Angela” was created, giving gender-based violence survivors a lifeline to safety, hope and freedom when they ask the simplest of questions: “Is Angela here?” The phrase has become a safe code for women who are experiencing gender-based violence and are reaching out for help.

“WOMEN IN ABUSIVE RELATIONSHIPS OFTEN HAVE THEIR ACTIONS CONTROLLED AND MONITORED.”

— Jennifer Hutton

The original idea, which began in 2016, was created in the U.K. by District Commander for Bassetlaw, Inspector Hayley Crawford, who named the initiative after Angela Crompton, a good friend who was killed by her husband in 2012.

Pascal Niccoli, pharmacist and owner of the Shoppers Drug Mart in the Conestoga Mall in Waterloo, Ontario, first heard about the “Ask for Angela” initiative at a conference he attended.

The idea resonated with him because in his work with community organizations where the focus was on women’s health and intimate partner violence, he observed a noticeable increase in intimate-partner violence and worsening of women’s health, particularly during the pandemic.

“I heard about pharmacists getting involved in a U.K. initiative called ‘Ask for ANI,’ [Action Needed Immediately],” Niccoli says. “The program was rolled out in bars and clubs where women might feel unsafe. Asking staff for Annie became code for ‘I need help.’ I felt this idea could be of assistance in my community and fairly easy to implement, so I brought the idea to Jennifer Hutton and her team at Waterloo Region’s Women Crisis Services to get their buy-in before taking it to Loblaws head office.”

When he did, Niccoli discovered that Loblaws was already involved in the Toronto “Ask for Angela” initiative, which was launched on National Human Trafficking Awareness Day on February 22, 2023.

Loblaws and its affiliates, which include Shoppers Drug Mart stores, Real Canadian Superstore, No Frills, Valu- Mart, and Your Independent Grocers, are perfect options for this program because of their sheer numbers and accessible locations. These are stores where women go to get everyday necessities including food, diapers and prescriptions. In the Toronto area alone, there are 238 Loblaws, Shoppers Drug Marts and affiliated stores that support the “Ask for Angela” initiative.

“Women in abusive relationships often have their actions controlled and monitored, but going to a grocery store or pharmacy, places where she routinely goes, doesn’t ring a whole lot of alarms with her partner,” says Jennifer Hutton, CEO at Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region.

Along with a multi-unit transitional home and two domestic violence shelters (Haven House in Cambridge and Anselma House in Kitchener), Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region is one of the largest Violence Against Women (VAW) shelters in Canada. Each location is approximately 17,000 sq. ft. and contains forty-five beds, with one bed at each location specifically reserved for a human trafficking survivor.

“Half of our residents are often young children whose average age is eight and under,” Hutton says. “And so we work with the two school boards in our region to set up transportation to take the children to their home schools, whether that is by bus or taxi. If a woman comes to us from out of town because it is not safe to stay where she and her family are from, we register her kids at the school that is closest to the shelter. We have a dedicated child-and-youth team that facilitates this.”

Hutton says that there is a full range of wraparound services available at the shelters, including children and youth programming and a medical practitioner, dental hygienist and music therapist. Staff are on-site 24/7, and there is a chat line that provides crisis support.

“I WANT TO SHOW OTHERS THAT THEY CAN GO THROUGH WHAT I WENT THROUGH AND STILL COME OUT THE OTHER SIDE, BUT IT IS NOT EASY.”

— Colette Martin

“One of the many success stories that I love from our music therapy program is how it helped a child build confidence and manage his stuttering. We also had a child who was selectively mute and did not speak due to his trauma who was able to eventually express his feelings through music,” Hutton says. “We have a consulting psychologist — which is unique to our shelter — who has been instrumental in helping women who have been involved in domestic violence and have suffered traumatic brain injury, which research shows is becoming more prevalent. This type of injury can affect overall executive functioning and how information is being processed.”

Carly Kalish, Executive Director of Victim Services Toronto, states that of the 18,000 clients her organization looks after annually, 70 per cent of them in Toronto alone are survivors of gender- based violence. “The majority of gender- based clients we support are survivors of intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and sexual assault,” Kalish says. “Along with an increase in the stats around gender-based violence, we are seeing an escalation in the violence against the clients we are supporting, including more strangulations and more damage to bodies in terms of physicality.”

The reasons as to why women do not report abuse vary. Along with the stigma and shame there are the day- to-day challenges, which include the inherent changes and upheaval, reliance on a partner for financial support, food insecurity, child care and the fear of what their partner might do to them or their kids if they report the abuse or flee the home.

“The most important thing for people to know is that we operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Kalish says. “Simply pick up the phone and call us. We will meet you in the community and help you navigate any system or barrier that is there relative to your leaving. We have access to funding if the criteria are met. If you are in a place where you are not ready to leave, we will support you regardless. We walk alongside survivors until services are in place to rebuild their lives.”

As a part of that support system, Kalish says they also have a trauma dog, Penny, a Labrador retriever who often goes to court to comfort children and women who are survivors of gender-based violence.

In partnership with the Toronto District School Board, Victims Services Toronto runs Teens Ending Abusive Relationships (TEAR) programs, which begin in elementary school and go right through high school. “Parents can help educate their kids by connecting them with programs such as our Youth Symposium, a virtual event that takes place on Feb. 22, which is the Day to End Human Trafficking. Last year, we had 22,000 attendees,” Kalish says.

“Ask for Angela” information flyers are posted in Shoppers Drug Mart and Loblaws stores and their affiliates, as well as in bathrooms and staff rooms.

Numbers show that the message is resonating with women who need help.

“In the past year, we have had more than 400 survivors reach out to us after accessing our contact information through the QR code on our posters,” Kalish says.

Hutton states that at least two women have accessed the service in the Waterloo Region, with one woman using the region’s crisis services shelters.

Standardization and training are integral components of the “Ask for Angela” campaign, which includes a comprehensive online tool and a corresponding video and manual. There are also brief huddles at the beginning of store shifts to remind staff about the program.

Kalish states that when a woman accesses Victim Services Toronto a safety plan is tailored to her specific needs, including an alternative place to live if she is ready to leave the shelter.

“We do a needs assessment to make sure that she has access to finances that aren’t connected to the partner,” Kalish says. “In the case of human trafficking survivors, we often replace their phone, which is frequently tracked or cloned. Mostly, it is about assessing the safety of these survivors and putting the necessary things into place.”

What is of overriding importance is for a woman to know that she is not alone and that help is available 24 hours a day.

“Even if it is the middle of the night, we will accommodate you,” Kalish says. “Police do not have to be involved in order to access help.”

Niccoli states that staff are assured that there are no expectations for them to become crisis responders or social workers. “The only expectation for a staff member is for them to bring the person asking for Angela to the appointed person in the store, who will then take them to a safe place and make the call to the Women’s Crisis Centre,” he says.

Another program that supports and highlights positive outcomes for survivors of gender-based and intimate partner violence is the She Is Your Neighbour podcast, which is hosted by Jenna Mayne and produced by Lillie Proksch, both from the Women’s Crisis Services of Waterloo Region. Launched in 2020, the She Is Your Neighbour podcast currently garners about 4,000 trackable downloads per season.

“For some of our guests it is the first time that they’ve shared their story, and it often gives them a sense of empowerment to move forward, to close this chapter of their life, and quite possibly become an advocate for others experiencing the same circumstances,” says Proksch. “The images of the guests in the podcast are changing the narrative on what gender- based violence survivors look like. Instead of the traditional dark and violent images, our guests are captured in powerful poses as they look directly into the camera.”

One of the women highlighted in the “She Is Your Neighbour” documentary is Colette Martin, whose ex-boyfriend broke her door down one night, then slashed her throat and stabbed her 37 times.

“After dating him for seven months I allowed him to move in with me,” Martin says. “It didn’t take long for me to realize that the person I thought he was was all a façade. He would go into rages over simple things and he tried to isolate me. I guess he just couldn’t fight who he was anymore. He tried to control the people I saw, the food I ate, the places I went. I had never heard of narcissism or coercive control until I met him. And I had never had any experience around any kind of domestic violence.”

After one incident, when her ex kicked her violently in the stomach, Martin retreated to the shower, where she cried for hours. She knew then that their relationship was over.

Although her ex moved back to Montreal and was in a new relationship, he continued to call and harass Martin. He eventually moved back to New Brunswick and contacted Martin, demanding that she return the rest of his things — items that he had originally told her to keep.

Whether it was foreboding or instinct, on May 1, 1997, an evening that will forever be imprinted in her psyche, Martin invited her cousin to spend the night.

“We were all in bed, including my six- year-old son,” Martin says. “My ex, who had been a no-show earlier in the evening, arrived at my house and kicked the door down. ‘Tonight is the night you are going to die,’ he told me.”

After her ex slit her throat, Martin was able to get away but he dragged her back. She escaped again, this time fleeing to her parents’ house, where her ex caught up to her in their driveway.

“I begged him for my life,” Martin says. “I was worried that he would kill my parents.”

Telling her that they were going to die together, her ex then proceeded to cut his own wrists and slash his throat.

As the police arrived, Martin grabbed the knife from her ex, who then told officers that Martin had attacked him. This was quickly contradicted by witnesses.

Alarmingly, a plastic surgeon Martin saw after the incident asked her what she had done to deserve the attack. “He said to me ‘Things like this don’t happen to good girls,’” Martin says.

“We don’t need blame when we are going through something like this. What we need is support and compassion. And that is not what I got. We already blame ourselves.”

At the court case, which took place with astonishing speed on June 27, 1997, the surgeon who’d looked after Martin at the hospital testified that if the cut on her throat had been half an inch closer to her jugular, the vein would have been severed. “It’s a miracle I’m still alive,” she says.

While she doesn’t remember much about the trial, Martin says that it was an extremely traumatic experience when she had to identify her ex in the courtroom.

Sentenced on August 15, 1997, to nine years for attempted murder and two concurrent years for break and enter, Martin’s ex-boyfriend was out of prison in six years.

While in prison, Martin’s ex tried to commit suicide. He had listed her name and phone number as next of kin but thankfully the call from the hospital was intercepted by Martin’s parents.

“I felt that I was the one who got the life sentence,” Martin says. Lawyers for her ex-boyfriend appealed his sentence on the grounds that the trial judge put too much weight on premeditation as an aggravating factor.

The New Brunswick Court of Appeal in denying the appeal found that “the trial judge did not put undue emphasis on this factor.” Martin’s case is now being studied by the students in New Brunswick Community College’s Police Foundations course.

“Over one hundred Ontario municipalities, including our region, have declared gender-based partner violence an epidemic,” Hutton says. “The realization that gender-based violence is a social issue is crucial, as is education and being familiar with the steps you can take to help someone you think is experiencing domestic violence. It is important to break the cycle of domestic abuse and violence, and that’s why we go into schools and talk to young people about the importance of healthy relationships.”

While Martin says she is in a good place now, jagged shards of pain still resonate in her voice. Nonetheless, it has been and continues to be important to her to share her story so that other women can recognize the red flags in abusive relationships, find a safe person to share their dilemma with and make the all- important safety plan to leave.

“I want to show others that they can go through what I went through and still come out the other side, but it is not easy. We need to get the message out there so that other women will want to share their stories, too,” says Martin, who received the Hall of Fame Award by the Crime Prevention Association of New Brunswick, in December of 2024, in recognition of her advocacy for safety, justice, and support for New Brunswick survivors.

“If I would have had someone like me to relate to it would have really helped me to heal. We can’t stay silent anymore. Silence is harbouring our perpetrators. Your voice matters; your life matters. We hear you; we believe you; we see you. Don’t give up.”

Kalish encourages any corporations who want to join the “Ask for Angela” initiative and provide additional resources should contact Victims Services Toronto.

Women’s Crisis Services Toronto 24/7 hotline number is 416-808-7066.

Anyone looking for help or more information can go to: victim services toronto

Women’s Crisis Services

Femicide-in-Ontario-December-2024-English.pdf