Frank Gehry: The Penultimate Visionary

Frank Owen Gehry is a Pritzker Architecture Prize winner, an award which embodies significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.

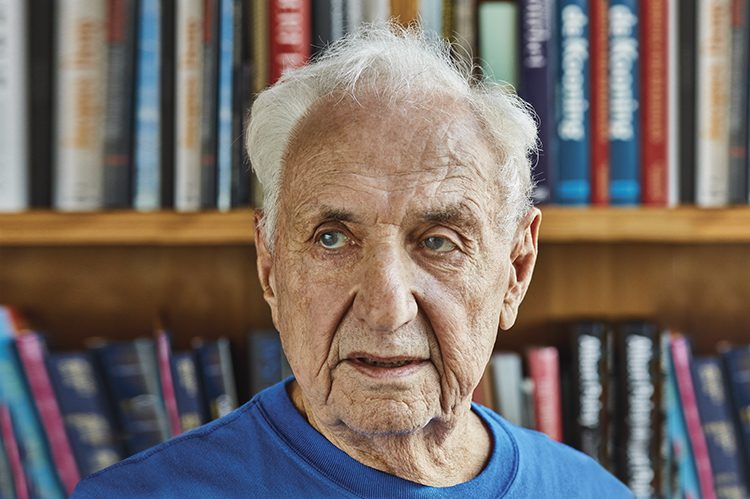

What makes someone a genius? Is there a creative or intelligence gene that is passed down through the hierarchy of generations, one that inspires and gifts the virtuoso with an attitude for inventiveness and a flair that most of us can only dream of? For Frank Owen Gehry, a Canadian-born architect who’s been living in the United States for seven decades, the moniker of genius centres on the continuum of going beyond, envisioning the extraordinary with a seismic unconventional and revolutionary mindset and approach. The natural capacity for exceptional excellence, manifested through one or more genres, is definitive of genius status, one with which Gehry (now 90 years old) is clearly gifted.

Gehry’s foray into brilliance began when he was only four years old. He was shown a photo of a Greek charioteer that dated back to 500 BC. Its sustainable beauty made him cry, and even at that earliest of ages, the impact was such that the young boy decided then and there what he wanted to do — create buildings that would move people five hundred years out.1

Born in Toronto in 1929, Gehry (who changed his name to Goldberg from Gehry when he moved to the United States), along with his parents, Irving and Thelma, and his sister, Doreen, lived both in Toronto and Timmins, Ont., for much of his childhood and teenage years. He always had a sense of being an outsider, which could be somewhat attributed to his Jewish and Polish heritage and the fact that anti-Semitism in Toronto was then a prejudice that was quiet but sometimes real. His maternal grandparents, Sam and Leah Caplan, owned a hardware store on Toronto’s Queen Street West, where Gehry would often go to “immerse himself in the wonderland full of screws and bolts and hammers and nails and every household gadget, all of it the stuff of possibility in Frank’s mind.”2

In 1949, when Gehry was 20 years old, he moved with his family to Los Angeles to see if the more temperate climate would help his father’s ill health. After achieving his bachelor of architecture degree from the University of Southern California in 1954, Gehry went on to study at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, which he left before graduating. Gehry’s imagination and creativity were burgeoning and he needed to begin crafting his career, which began with his Easy Edges furniture line (1969–73) that was shaped by the layering of corrugated cardboard material. It was the beginning of the architect’s fascination and love for using prefabricated and unconventional materials to create, which included everything from plywood to titanium. Gehry’s life direction was set, one that was and is deeply rooted in the forms, shapes and spheres of architectural excellence. Between 1984 and 1986, Gehry designed a collection of fish-shaped lamps, which led to large public sculptures, such as Standing Glass Fish (1986) and Fish Sculpture (1989–92). Along with designing the official World Cup of Hockey trophy, Gehry also collaborated with Tiffany & Co. on a series of jewelry collections. In 1992, he also launched his Bentwood furniture line, with eclectic pieces moulded from wetted and then bent wooden slates, with a provenance that was ensconced in the Indigenous arts and crafts of Pacific Northwest artists.

Inspired to create a home for his second wife, Berta, whom he married in 1975 (Gehry divorced his first wife, Anita, in 1956), Gehry took on the renovation of his pink-clad old Dutch colonial bungalow in 1978, which was located on a highly visible Santa Monica, Calif., street. Eager to imprint his signature avant-garde stamp on the house, Gehry used a collection of his now-familiar non-traditional building materials, including metal, glass, plywood, corrugated metal and chainlink fencing to reinvent the interior.

Of course, he left the outside of the house clad in its cloak of pink. Although the neighbours were not ecstatic with what some considered a design atrocity, Gehry’s street was suddenly awash with students who came to marvel at his work. And while many of Gehry’s business clients were also not impressed with the new direction he was taking, private clients loved the new and bodacious edgy spirit of his work.

The project, however, that brought Gehry (who was then 68 years old) to international fame, one that is now famously referred to as having the “Bilbao effect,” is the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, located in Bilbao, Basque Country, Spain.

The museum, named one of the most important works completed since 1980 by the 2010 World Architecture Survey (as named by architecture experts), was officially opened in October 1997 by King Juan Carlos I of Spain. The base of the Guggenheim building is limestone, and the building itself is clad in titanium plates (the exterior alone has 33,000 plates).

The Natural Capacity For Exceptional Excellence, Manifested Through One Or More Genres, Is Definitive Of Genius Status, One With Which Gehry (Now 90 Years Old) Is Clearly Gifted

And while the building houses approximately 250 pieces of contemporary works of art, it is the shapes, the sharp angles, the concave walls and hoods, the flap extensions and Christmas bow-like top that draw the thousands upon thousands of tourists to marvel at the building, as it gleams radiantly under both the bright Spanish sunshine and the benevolent lights of night. In fact, the famed American architect Philip Johnson called the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao “the most important building of our time.”

Frank Gehry Is A Maestro Of Material Manipulation Magnificence, A Seer Whose List Of Billowing Accomplishes Leaves Architects And Creators Of Every Ageawestruck

More grand-scale projects ensued for Gehry, with the jewel in the crown (and certainly viewed as being in the same vaulted sphere as the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao) being the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. Opened in 2003, it and was initiated by Lillian Disney, the widow of the seminal and influential creator and visionary Walt Disney. Originally planned with a stone exterior, the concept was changed to clad the building in stainless steel because of the stunning effect it evoked with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Because of this change, Gehry was able to shape the exterior to reflect the dramatic silver sails that billow and jut out from various angles of the concert hall. The lobby is described as being a “transparent light-filled living room for the city,” with seating that breaks down the disembodiment of balconies and instead provides audiences with intimate views of the musicians and conductors, while providing acoustics that are second to none.

Gehry’s appreciation of music is such that he compared his Atlantic Yards project (in Brooklyn, N.Y.) to Bach, a composer and musician that Gehry loved. “I look at it like composing a Brandenburg Concerto, which has a coda but layering. It builds up notes as it goes and then it shifts into another octave. It adds different instruments and changes the character as it unfolds,” Gehry shared with author Barbara Isenberg.3

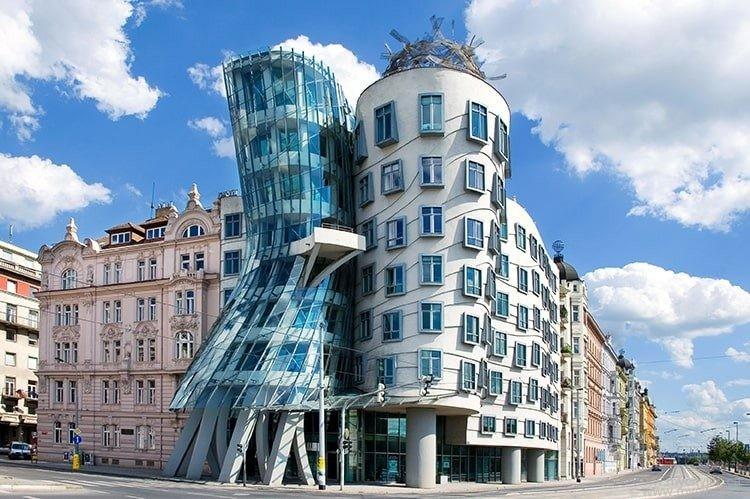

Indeed, Frank Gehry is a maestro of material manipulation magnificence, a seer whose list of billowing accomplishments leaves architects and creators of every age awestruck. Collaborating with prestigious institutions, including museums, concert halls and libraries, Gehry has worked all over the United States, Europe and China. In 1999, he built the aluminum-covered Frank O. Gehry business building complex in Dusseldorf, Germany. This was followed by the Music Experience Project in Seattle, which is a $100-million interactive rock and roll museum. The Dancing House building in Prague is a collaboration with Vlado Milunic (1996).

The vast majority of critics concur that Gehry’s buildings are singular; there is no credible architect on the horizon who considers ideas in the way they are presented, then moves forward with a vision to recreate in a manner that only Gehry can imagine. That being said, Gehry admits that at the start of each new project, he is filled with a sense of angst. Admittedly, however, after all these years he is able to tap into his deep well of inner confidence.

Some of the projects that illuminate Gehry’s penchant for the unusual (some have even called his designs “weird” or “bizarre”) include the 1991 Chiat/Day Complex in Venice, Calif., (aptly called the “Binocular building”), where hundreds of Google employees work on optimizing their daily searches. The Olympic Fish Pavilion in Barcelona, Spain, is a shimmering gold and steel-mesh fish edifice created by Gehry for Barcelona’s 1992 Olympic Village.

There Are Only A Handful Of Architects Who Have Attained The Celebrity Status That Frank Gehry, Winner Of The Prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize And A Companion Of The Order Of Canada, Has Garnered

The IAC Building, New York City, represents two firsts for Gehry: his first Manhattan building and his first major glass building (2007). Foundation Louis Vuitton in Paris (2014) has 12 glass sails on its ship-like exterior. The not-to-be-missed Biomuseo, Panama City (2013) looks like a throwback to Gehry’s childhood fascination, with huge coloured blocks that are magnified in bright red, blue, green and yellow hues. Closer to home, Gehry, as he approached his 80th birthday, renovated Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario building, which was originally built in 1918.

There are only a handful of architects who have attained the celebrity status that Frank Gehry, winner of the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize and a Companion of the Order of Canada, has garnered. One of them is Frank Lloyd Wright, who influenced Gehry’s earlier works. But none of this seems to go to Gehry’s head, who famously said that he is not interested in being considered an artist, but instead, a deeply rooted architect. With a dry sense of humour and a deep sense of whimsy, Gehry has played himself on the television series The Simpsons and in ads for Apple. He is the subject of director Sydney Pollack’s 2005 documentary Sketches of Frank Gehry, which focuses on Gehry’s work and legacy.

While Frank Gehry has lived in the United States for several decades, Canada’s love and respect for the Toronto boy who has achieved such extraordinary heights, such extraordinary accomplishments, was celebrated in a November 2019 ceremony, where he was a Canada’s Walk of Fame inductee. Along with the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal Award, Gehry was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama in 2016.

Sources:

1. Fortune magazine, October 2018.

2. Goldberger, Paul. Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank

Gehry. New York: Borzoi Book/Alfred A. Knopf, 2015.

3. Ibid.