Margaret Atwood – A Life Shaped By Words

Margaret Atwood doesn’t like being put on a pedestal, but that’s where she seems to always find herself.

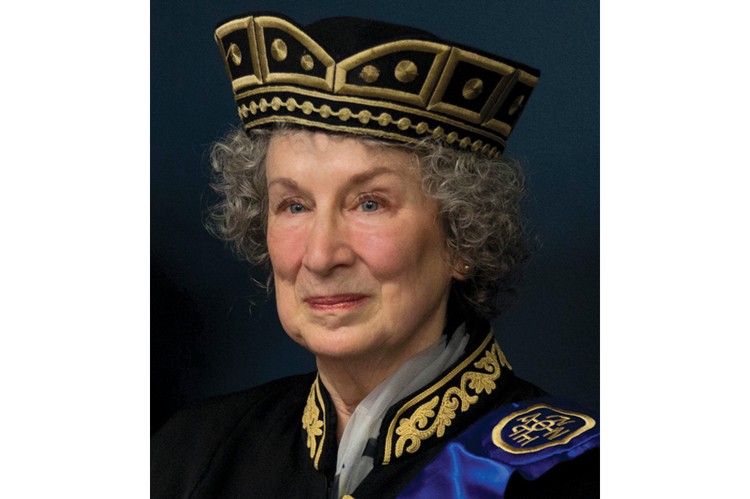

Seated in the consul general’s office in the back of the Greek consulate in Toronto, away from the last remnants of a lingering crowd that gathered to watch her receive an honorary PhD from the University of Athens, Atwood explains the problem of idolization. “The thing about pedestals is there’s very limited floor space; there isn’t much room to move around,” she says. “Given my choice between being on a pedestal and having fun, I’d rather have fun.”

She’s calm and friendly, even though for the last hour or so she’s entertained an endless procession of photograph seekers, autograph requesters and a few Just-wanted-to-tell-you-how-amazing-you-ares. In the past she avoided the “icon” label like a humanity-annihilating plague, but it appears her fans don’t seem to care: she’s going on that pedestal.

She leans in and whispers, “That’s because you get really, really old.”

Good one, but hardly. It takes more than having grey hair to achieve her level of success and respectability. Perhaps in her autumn years she’s warmed to the idea?

“What, being old?”

(Ha!) Being an icon!

“It’s not really a Canadian thing,” she says (“unless you’re a hockey star”). “I think it’s always something we have an ambivalent feeling about, maybe we’ve read so much Greek mythology — ‘Call no man happy until he is dead’ — and you never know what twist the story will take.”

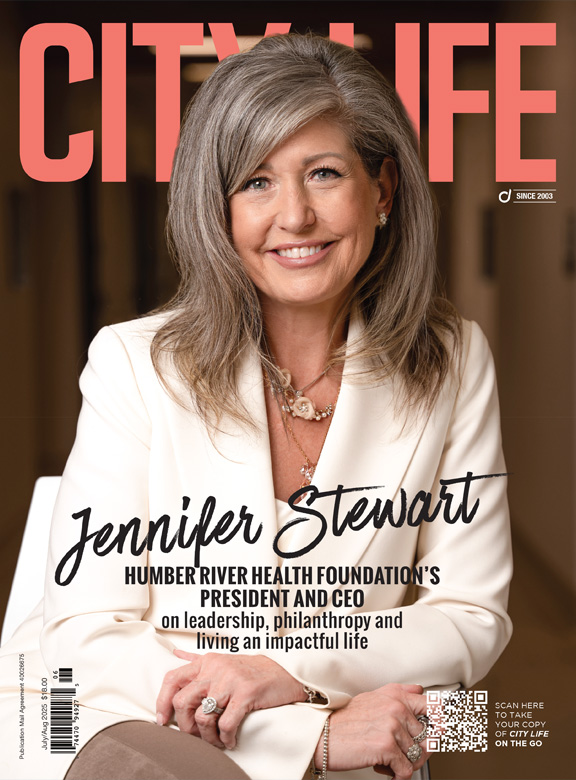

A couple of hours ago the Canadian author, poet and all-around literary rock star was seated at the focal point of a room full of her fans, packed like too many sardines in too small a can. She wore, as she does now, the gold-embroidered doctoral gown of the University of Athens, ready to receive an honorary PhD from the university’s Faculty of English Language and Literature. She’s the first Canadian to receive this distinction, and Greek ambassador Eleftherios Aggelopoulos was singing her praises. She’s “one of the best minds of our time,” he said, a writer who produces works of “universal relevance” filled with “complex thought and flow.”

Calm, attentive, Atwood accepted these commendations with grace and gratitude, even if she’s heard it all before. She’s enjoyed a long and fruitful career of 50-plus years, and much has been said about her over that time. She’s been dubbed an “author provocateur” and a “scintillating wordsmith,” a “prophet of doom” and the “Queen of CanLit.” Her work is lauded for its brilliance, perception and, quite often, its sharp wit. (Seriously, she’s really funny.)

“She’s a very protean writer,” says Robert McGill, assistant professor of English at the University of Toronto. McGill, also the author of The Mysteries and the recently released Once We Had a Country, explains that when it comes to her oeuvre there really is no quintessential Atwood work. “One of the interesting things about her,” he says, “is you never know what she’s going to do next.” She’s explored a variety of genres and themes, such as proto-feminism (The Edible Woman), identity construction (Cat’s Eye), totalitarian states (The Handmaid’s Tale) and the manipulation of nature (Oryx and Crake); travelled through the past, present and future; and played in all fields of the written word. While best known for her literature and poetry, Atwood has produced numerous short stories, essay collections, television scripts and librettos, even making a recent excursion into ebooks. She remains relevant and nimble, unafraid to dip into new ideas and trends — just check out how active she is on Twitter.

All these kudos are true, of course. The 74-year-old is one of the most highly regarded and decorated writers this country ever produced. Her CV is strewn with accolades, including two Governor General’s Awards (The Circle Game, 1966; and The Handmaid’s Tale, 1985), an Arthur C. Clarke Award (The Handmaid’s Tale, 1987) and the Man Booker Prize (The Blind Assassin, 2000) — and that’s merely scratching the surface. On top of the master’s she earned from Harvard’s Radcliffe College, Atwood’s also received well over 20 honorary degrees, including from Queen’s University, Oxford University and the Sorbonne. The PhD from the University of Athens is her first, however — an honour that “would make my old thesis adviser very, very happy,” she jests. It will be no surprise when she inevitably adds the Nobel Prize in Literature to the list, either.

While Atwood doesn’t know what twist her story will take, one thing is for certain. You never know where an interview with Atwood will go. Known for being blunt, critical and wielding a cold tendency to correct, Atwood’s intellectual agility regularly vaults her to smartest-person-in-the-room status. She can cut confidence to shreds with a few swift, sharp words, sending egos weeping back to Freud for a sympathetic “There, there.” She’s been a handful for interviewers ever since her early days in the spotlight. The “Ice Queen,” as the old moniker goes, embarrassed Hana Gartner on the CBC’s Take 30 back in ’77, suggesting the host stick to Harlequins if she longed for happy endings. More recently, in 2012, she gave Jian Ghomeshi a taxing time over “science” versus “speculative” fiction on Q. She’s an overwhelming, daunting creature — even though she can’t be more than 5-4.

All of this is true, to one degree or another. But it’s also an interpretation, a subjective and skewed framing of a woman who’s been read, discussed and written about for over five decades. “I’m not responsible for other people’s descriptions of me, unfortunately,” she said to Bill McNeil in a CBC interview in ’68. What was true then is true now. Whether they dub her the “Ice Queen” or the “Queen of CanLit,” any reporter or reviewer can hone in on whatever minute detail or subtle idiosyncrasy they please and run with it. It’s been happening to her for years, as it does to anyone with an ounce of fame.

But the truth, as Atwood knows, is subjective and illusive. She may be a shrewd and frank intellect, but she’s an accommodating woman, generous with her time. (And she’s funny. Did I mention she’s funny?) The point of something, she says, is not whether it’s true or untrue, “it’s whether it’s interesting or not as a foundation for stories.” She said this while discussing the debate around Robert Graves’ mythography The Greek Myths, but it seems to be a theme woven through the fabric of her life. What others say is out of her control. Besides, she isn’t one to dictate what should or shouldn’t be said.

“She’s not a propagandist,” says McGill. While Atwood has voiced her opinion on political matters in the past — including last year when she drew ire from many for joining Restore Our Anthem, a group pushing to change the lyrics of O Canada to something more gender-neutral — McGill explains that in her novels, “She doesn’t want to tell people what to think. She wants public dialogue, she wants civic debate, and if there is something that has connected her work over the decades, one of those things is that she’s repeatedly drawn attention to important issues in her text, whether it be women’s rights or the environment or the question of Canadian history, by prompting these debates.”

Indeed, Atwood stirs the pot frequently by creating narratives where stimulating ideas are left to unwrap and ponder; loose ends remain untied, inviting readers to bind them as they see fit. “I leave a space for them to decide what they would do in that situation,” she says, as in the endings of Oryx and Crake and Surfacing. “Or in the case of Grace Marks,” the main character in her novel Alias Grace, a historical fiction based on the controversial murder conviction of a Canadian maid, she adds, “did she or didn’t she? Since nobody ever knew for sure. You decide. You have to decide what to think.”

University of Athens professor Mary Koutsoudaki, who suggested Atwood for the distinction and made the trip overseas for the ceremony, explains that on top of being a “major figure in Canadian literature” Atwood offers fascinating perspectives of Greek mythology. In The Penelopiad, for example, Atwood presents a fresh retelling of The Odyssey, one that explores the double standards between men and women, from the perspective of Odysseus’s wife Penelope. “I find it also very lyrical in many ways and very interesting in the rehandling of the Greek myth,” Koutsoudaki explains.

Greek mythology has always been a major force in Atwood’s life. Due to her father’s work as an entomologist, Atwood and her family lived in the hinterlands of northern Quebec for a large portion of each year. Having no electricity and few toys, she read constantly, everything from Victorian literature to Grimm’s Fairy Tales to comic books. One comic in particular was Captain Marvel. Whenever the story’s protagonist Billy Batson spoke the word “SHAZAM” — an acronym for Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles and Mercury — he would transform into a superhero, Captain Marvel, imbued with the powers of those Greek gods (and, yes, she knows Mercury was Roman). Of course, Atwood had to study up on who they all were.

Back in those days students couldn’t take English literature without also taking an ancient language, such as Latin or Greek. Along with the Bible and European folklore, Atwood explains that Greek mythology is one of the “fundamental treasure chests of stories.” The works of Milton, 19th-century poetry, early opera and 18th-century French drama were all based on classic myths. You couldn’t study them without an ancient language. “And it was assumed that you would know that body of lore,” she says. It’s also why she continues to go back to it today: “There’s always a new wrinkle.”

Last year Atwood released MaddAddam, the finale to her dystopic speculative fiction trilogy, which was first laid out a decade ago in Oryx and Crake (a short lister for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction in 2003) and continued in The Year of the Flood. Many point to ideas and situations she’s outlined — biological manipulation (synthetic meat, bioengineered animals, etc.), all-controlling megacorps, pandemic viral outbreaks — and the eerie potential they have of coming to light. Some would say she has a keen ability to prophesize —

“No, I’m not a prophet,” she interjects. “I’m interested in the back pages of newspapers, interested in these little stories that then become big stories. So I’m really just poking around.”

But you’re perceptive, able to connect the dots.

“So, you have this many things that you say, this many things come true and people think you’re perceptive. It’s because people have forgotten about these ones that didn’t.”

Her speculative fiction poses questions, not predictions; presents possibilities, not inevitabilities. “The things in the books are in our possible futures. And to some extent they are within our control,” she says. “So, what kind of world do you want to live in? And what will you have to achieve or sacrifice in order to live in it?”

And besides, she adds, if you look at what’s being proposed and developed in the real world it’s not hard to put things together. She points to the announcement by Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos that the online retailer wants to use flying drones to deliver orders. “How much fun for target practise is that going to be?” she says. And what happens when birds take exception to flying robots gliding through their airspace? Or if one malfunctions, falls out of the sky, lands on your head and kills you? The answer seems obvious. “You say, ‘No, thank you.’ Don’t go there. Don’t even think about it.”

But some things aren’t so obvious. In late 2012, in an interview on George Stroumboulopoulos Tonight, Strombo asked a simple question: Which book should be taught in school? Atwood, after one of her common detours, eventually suggested something by Alice Munro.

“Is that what I said?” she asks.

Yes, and less than one year later it was announced that Munro won the Nobel Prize in Literature. How many schools will now make her work, if they hadn’t already, a regular part of the curriculum?

“Well, I wrote the introduction to her Selected Stories.”

You’ve known her for a while, then?

“Many years. Oh, since 1969. In fact, I was just talking to her on Sunday. She told me — No, let me see.” She pauses to think. “She left a phone message. It was snowing in Victoria. So I was talking to her on Friday.”

About?

But: time’s up.

It’s late in the evening after a long day and Atwood is being whisked away. Like so many of her novels, the conversation fades out on a cliffhanger. She’s laid the foundation and now it’s time to interpret. What will she think of this writing? Is this just another hack trying to construe a small quirk and present it in a never-seen-before fashion? One more wannabe with enough gall to take a crack at the riddle that is Margaret Atwood?

All of that is true, more or less.

But in the saga of Margaret Atwood, there always seems to be another chapter to write.

No Comment