Diagnosed to Die, Saved by a U.S. Doctor: Gregorio Di Pietro’s Incredible Story

After multiple surgeries, Gregorio Di Pietro received the help he needed at Ohio’s Cleveland Clinic.

His smile, all-encompassing and kind, is infectious. It is the kind of smile that leaves you with only one choice, which is to return his greeting with a smile of your own, happy to share his gratitude for the positive things in life. However, things have not always been this good for Gregorio Di Pietro, a 78-year-old Maple, ON., man who suffered nine invasive surgeries in four years.

To share his journey, one that has been fraught with frustration, despair and outsized pain, there is no one better to narrate it than Di Pietro himself.

“WE WANT THE PUBLIC TO BE AWARE OF WHAT IS GOING ON IN OUR HEALTH CARE SYSTEM. CHANGES NEED TO BE MADE.” – Lawrence Di Pietro

“I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in 1985,” Di Pietro says. “Still, everything was going along OK until Christmas of 2019, when I experienced a blockage.”

And that is when everything went off the rails for Di Pietro, his wife Carmela and their two sons, Lawrence and Gerardo. By the time he was triaged and processed at a major Ontario hospital, Di Pietro was told that he needed surgery — immediately.

“I relied on the doctors, so I agreed to go ahead with surgery and was given a temporary ostomy,” a surgery that created an opening (stoma) to allow stool to drain out of his body and into a pouch known as an ostomy bag. “But right afterwards, my medical team mentioned that the procedure might not have been necessary,” Di Pietro says, shaking his head in disbelief at the memory.

Di Pietro says he lived with the ostomy until the spring of 2020, at which point he had surgery to cut out the intestinal blockage and reattach the intestines, reverse the ostomy procedure and remove the bag.

Months later, however, Di Pietro was feeling unwell. Upon investigation, a leak in the reattached connection was discovered that required another series of operations and increased the amount of scar tissue in his gut.

“I was waking up in pain every day,” Di Pietro says. “I’d have surgery and then six months later I’d have another surgery. And then six months later I’d have another one. It was hard on me and it was hard on the family.” And disturbingly, after these multiple surgeries, Di Pietro says that his abdomen was essentially left open with his intestines hanging out.

“ONE OPERATION IN THE UNITED STATES FIXED A PROBLEM THAT NINE OPERATIONS IN CANADA COULDN’T.”

– Gregorio Di Pietro

The next four years can only be described as a living nightmare, so severely traumatic that near the end of this period Di Pietro wanted to end his life.

Because of his Crohn’s disease, Di Pietro suffered damage to his intestinal tract, which compromised the amount of nutrition his body could extract from his food, ultimately causing him to suffer from malnutrition. Because of this, he had to go on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), a intravenous treatment that provided him with the calories, proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals he needed while giving his inflamed intestines a chance to recover.

“The doctors told me that I was going to have to live on TPN for the rest of my life. But it was damaging my liver and kidneys, which wasn’t good. I went off TPN and then I couldn’t eat anything. By that point I only had a few months left to live,” he says.

The intimate details of what Di Pietro went through for all those weeks and months before, between and after the multiple surgeries are shared by his son Lawrence, who in the telling reveals the depth of the family’s suffering and how badly his father’s situation had deteriorated.

“Different nurses would come in and tape a bag around my dad’s open wound where his intestines were exposed, and every time he ate, liquid poo would come out of his belly and into the bag,” Lawrence says. Around the edge where it was fastened to his body, “the bag would almost always leak, which irritated and compromised his skin. Dad would lie in bed in that state, waiting for the nurse to come back and clean him up before applying a new wrap around the wound.”

This situation went on for a couple of years, and after the ninth surgery Di Pietro’s medical teams at two Toronto- area hospitals told him that they couldn’t do anything more to help him.

The Di Pietro family was devastated.

“It was bad, really bad — I was looking for ways to end my life,” Di Pietro says, a statement that is hard to believe coming from the man dressed in a crisp blue and white polka-dot shirt, whose grey square-framed glasses don’t conceal the determination in his eyes. In fact, when he walked into the kitchen of his classic Italian-Canadian home — all-white cupboards, an espresso machine on the counter and a glass cake dome covering a bowl of delectable cioccolatini e pasticcini on the kitchen island — it is uplifting to see how far he has come.

The Di Pietro family, close and loving, advocated for Gregorio every step of the way. Indeed, throughout our conversation, his wife Carmela hovers quietly in the background, a pillar of support as she contributes details here and there to the conversation, ones that she feels are important to understand the family’s journey. Gregorio smiles at her warmly, his appreciation evident in the way he listens intently to what she is saying.

“My parents have been through an awful lot — they lost a child, my older sister, who was ten years old when she died,” Lawrence says. “They almost lost their house when the mortgage rates jumped from five per cent to close to 20 per cent overnight, and yet my dad stayed strong. For my dad to say that he wanted to take his life was devastating.”

And so, when the family was informed that Di Pietro’s situation was grave — that he had a projected three months to live — Lawrence Di Pietro sprang into action, taking it upon himself to search the Internet for any and all possible solutions that might help his dad.

“My son told me not to give up hope, that we were going to get a second opinion,” Di Pietro says. “Carmela told me to hang in, that she would help me. I was so tired, but I kept going for the family.”

During his research Lawrence kept coming across the names of two clinics in the United States that specialized in intestinal surgeries, one that was in Los Angeles and the other in Cleveland, Ohio. “This was our last chance, so I reached out to the Cleveland Clinic, because it was closer to home,” he says.

During this time Di Pietro had been communicating with the Ontario Ministry of Health, who in a letter informed him that his medical treatment did not meet the “regulatory criteria” for what the province deemed an emergency. “How could it not be an emergency? I was told that I only had a few months to live!” Di Pietro says, his tone a mix of disgust and disbelief.

And so, with his health failing, the only way forward that the family could see was to take out a $600,000 line of credit against their family business. “We had no time to pursue other financial arrangements,” Lawrence says. “We got the loan and are currently dealing with the taxes relative to that.”

“I WAS HIS LAST HOPE TO GET HIS LIFE BACK ON TRACK.”

– Dr. Kareem Abu-Elmagd

Di Pietro’s records and medical history were sent to the Cleveland Clinic and discussions ensued.

“The clinic’s medical team told us that they thought they could help my dad — with ‘thought’ being the operative word,” Lawrence says.

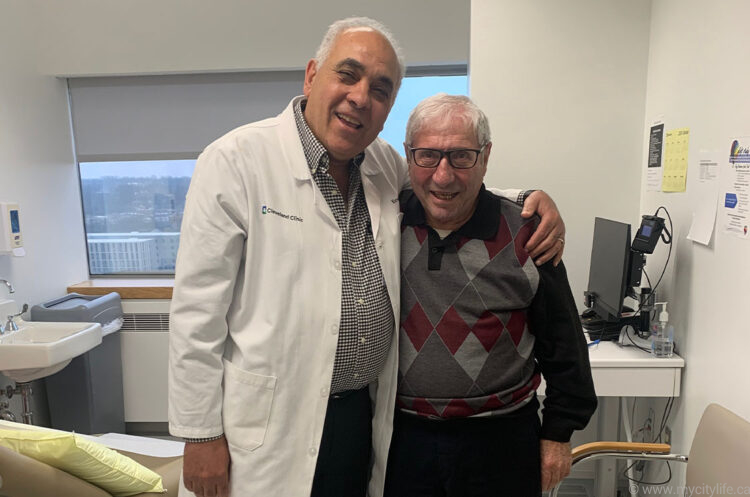

Enter Dr. Kareem Abu-Elmagd, a highly skilled surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic who has an international reputation for clinical and technical contributions in the field of transplantation and specializes in abdominal organ transplantation and digestive-system surgery.

“It was a risk going to the States, but nobody could do anything up here for me, so we took the chance,” Di Pietro says. “I told Dr. Kareem that I couldn’t have any more surgeries, that I had too much scar tissue. He told me that he had heard that before. He also told me that what I was going through was not living. ‘I can make you better,’ he told me. ‘I don’t know how much better, but I can help you.’”

After a couple of interviews between Dr. Abu-Elmagd and the family over Zoom, Di Pietro, Carmela, and their son Gerardo travelled to Cleveland, where Di Pietro spent a pre-surgery week having tests done that would inform the plan for the eleven-hour surgery that Dr. Abu-Elmagd would perform.

“Di Pietro was desperate when he first came to see me. He was crying,” Dr. Abu- Elmagd says. “And when I see a man cry, it breaks my heart. Di Pietro had severe chronic Crohn’s disease and short bowel syndrome, which means he didn’t have enough bowel to absorb the daily caloric and nutritional needs necessary, which is why he needed TPN. He also had an obstruction in his bowel as well as fistula, an abnormal connection that develops between the intestinal tract or stomach and the skin, which affects the healing process. Reconstruction was tough and requires the kind of technical skills that not every surgeon is able to acquire. I was his last hope to get his life back on track.”

In January of 2024, Dr. Abu-Elmagd performed a major reconstruction of Di Pietro’s gastrointestinal tract.

“Di Pietro required lengthening of the small bowel along with a serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP),” Dr. Abu-Elmagd explains.

While Di Pietro was recovering, Carmela stayed at a long-term rental that was affiliated with the clinic. Lawrence and Gerardo took turns travelling to Cleveland to see their dad and support their mom.

“The whole process, from the time my dad went to Cleveland until he was able to come home, took six to seven weeks,” Lawrence says. “By that point, his wound was closed and he no longer needed an ostomy bag.”

Says Dr. Abu-Elmagd, “Di Pietro is currently living a normal life with the reconstruction work and is a fully functioning, productive citizen.”

During the past six to eight months, Di Pietro has been trying unsuccessfully to get the Ministry of Health to reimburse the family for their out- of-pocket $600,000 in expenses. His thoughts and emotions regarding what he and his family went through, the financial burdens it caused and the fact that the Ontario health care system did not come to his aid during one of the most challenging times of his life are all part of why he has decided to share his story publicly.

“Why can’t we get the same kind of health care here that I got in the States? Our health care system is out of control; we can’t keep going on like this,” Di Pietro says, shaking his head in dismay. “We lost so many of our doctors years ago because of the crackdown on extra billing. These doctors go to school for many years — they should have the right to charge extra, to bill for what they are worth. I have paid health care taxes all my life. I feel that I should at least get some of my expenses covered. I think we need to do what a lot of countries are doing and that is to have a private sector of health care in addition to the system of public care we have now. If we work together and speak with our politicians, if we are motivated, we can find solutions. If no one gets involved, nothing gets done.”

Lawrence Di Pietro also is upset with the state of Ontario’s medical system, which he says is underfunded and understaffed.

“I cannot emphasize strongly enough how bad my dad’s situation was,” he says. “I don’t know how he did it, to be honest, because it killed us. We lived it, we saw it and we want the public to be aware of what is going on in our health care system. Changes need to be made.”

When asked if the family would do it all over again, including taking on such a major financial burden, Lawrence’s answer is both simple and anticipated by anyone who has ever walked the path with a loved one who is gravely ill.

“Of course,” Lawrence says, without a sliver of doubt in his voice. “My dad is back to being his happy self. He comes into work a few hours most days, and over Christmas last year he was able to take a vacation to Florida. He is just happy to be alive.”

Dr. Abu-Elmagd, who consulted pre- and post-surgery with Di Pietro’s Toronto doctors to ensure that he continues the medications that help manage his disease, is dedicated to sharing his expertise with doctors around the world, including those in Canada. He is currently teaching colleagues his innovative gut reconstructive surgery and how to perform what is known as “Kareem’s Procedure.”

“‘Kareem’s Procedure’ is a surgical correction of the gut malrotation, which is a congenital anomaly whereby the intestine was not placed in its normal position. It is a condition that carries the prohibitive life-threatening risk of volvulus, a twisting and cutting off of the blood supply of the intestine. With the new ‘Kareem’s Procedure,’ the misplaced intestine is fixed into its normal position, thus preventing the twisting of the bowel. The procedure has been 100 per cent successful in both my adult and children patients,” Dr. Abu-Elmagd says.

“Canada has many wonderful surgeons, but when someone is experiencing challenges with Crohn’s disease and their case is complicated, it is necessary to seek outside advice from a surgeon who specializes in the disease. With universal access to social media, patients should make sure to source additional help if they are not happy with their care,” and once they receive the proper treatment, they must be compliant with the prescribed course of treatment, says Dr. Abu-Elmagd.

Today, Di Pietro’s appreciation for Dr. Abu-Elmagd continues to be immeasurable. “It is amazing what Dr. Kareem did for me. I am normal now and I’m happy. I can eat whatever I want. I can go to work. I couldn’t be any better,” Di Pietro says, and in his megawatt smile you can capture a glimpse of what he was like as a young man. The warmth of that smile floods the room with positivity, delight, and a genuine gratitude for getting a second chance at life.

Indeed, it is the kind of smile that stays with you long after you’ve said goodbye to this extraordinarily courageous family.

INTERVIEW BY MARC CASTALDO