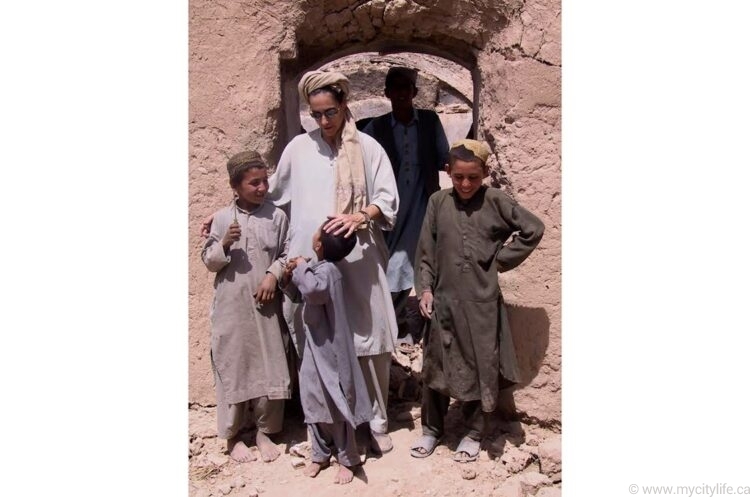

The Plight Of The Afghan People

With the pullout of American troops and personnel and the recent Taliban takeover, Afghan people are both bereft and fearful for their future.

The images and live video streams documenting the frenzied scene at Afghanistan’s Kabul airport on August 16 are such that, once seen, they are impossible to forget, involving inconceivable moments of human suffering, tragedy, fear and despair.

Hundreds of Afghans — most of whom appeared to be men dressed in their traditional clothing of a perahan tunban (shirt/pants) — ran desperately alongside a U.S. Air Force Boeing C-17 plane in hopes that by their very efforts the pilot would turn the aircraft around and shepherd them all aboard. One image shows a man climbing upwards towards what looks like a small vent on the side of the C-17 airbus, his very being emitting the hope that he might be able to wiggle through its opening. At least a dozen people stood on the landing gear while others clung to the wings of the departing plane; eventually, two people tumbled to their deaths when the Boeing aircraft took to the skies. Anyone who saw these images will forever have them tattooed on both their heart and their memory bank.

Fleeting snapshots of the interior of one of the evacuation planes leaving Kabul showed an estimated 640 people aboard, double the suggested payload. In the midst of this chaotic milieu, Ashraf Ghani, the elected president of Afghanistan, fled with his inner circle to the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The story of Afghanistan is a complex, multi-layered history of insurgency and occupation, a country whose people carry some of the blame for what has gone wrong, but also a country that has been steeped in rampant corruption and manipulated by its neighbour, Pakistan, with whom it shares a 2,430-km border along its southern and eastern edges.

After two decades of U.S. forces on the ground in Afghanistan — 2001 to 2021, which followed a decade of Soviet control dating from 1979 to 1989 — in just a short period of time, one that is measured in weeks and months, the ragtag group of militants that make up the Taliban seized control of Kabul, the country’s capital and the central hub of the Afghanistan government. The timing of the Taliban’s August 15 takeover of Kabul was both pragmatic and relevant, as the United States prepared to withdraw their military forces and cease all operations by August 31, 2021.

“How dare the world walk out on the Afghan people like that? How dare they?” asks Sally Armstrong, a journalist, human rights activist, author and Amnesty International award winner, who first started reporting on Afghanistan in March of 1997. “Where are the Afghan people going to get food? They dare not leave the house. People don’t want to be seen bringing food because it looks like they’re harbouring someone, and the Taliban are going door-to-door. My fixer sent a video of them executing a guy down the street from him. It’s so awful. I’m absolutely gutted.”

The evacuation efforts to get Afghans out of their country involves a host of countries, including Canada, Britain, Australia and the United States. Since August 14, the United States has facilitated the evacuation of over 100,000 people. Canada has evacuated 3,700.

As Afghans crowded, mostly maskless, outside the Kabul airport — some sitting on slabs of rough concrete while others stood, some deep in a sewage canal, at the ready, hoping to catch a glimpse of whatever hope might be floating beyond the margins of the fortress-like wall — an extremely devastating event occurred. On August 26, a huge explosion at the Kabul airport killed an estimated 170 Afghans, with at least another 200 Afghans wounded. Also, 13 U.S. service members were killed and 15 U.S. service members wounded. It was one of the deadliest incidents for U. S. service members in a decade.

How, one is forced to ponder, can a disparate group like the Taliban take control of a country in such a short period of time with virtually no pushback from that country’s militia?

“There’s never been a war fought in the history of the world where one small, fairly ragtag band walked across the country and knocked everyone off,” Armstrong says. “Why isn’t anyone talking about who got paid off? Why isn’t anyone talking about how much money was given to the Afghan army members to disappear, members who hadn’t been paid, by the way? It was such a set-up. How many deals were made with the army, with the tribal elders, with the warlords?”

Corruption is an unequivocal thread that weaves all levels of Afghan society together in a tight cycle of payouts and protection.

Sarah Chayes, a former NPR (National Public Radio) reporter who left journalism and stayed behind in Afghanistan for years concurs:

“I was on the personal staff of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff working in Washington, in the Pentagon, with top secret security clearance,” Chayes says. “As a part of the interagency process, in 2010 it was decided that we should have a policy around corruption. But in 2011, a decision was made that in fact we were not going to address it. That the only corruption that should be addressed was the corruption perpetrated by the police, which was the responsibility of the military, thus absolving the State Department of any responsibility.”

“Pakistan, and I mean the military, the de facto rulers of Pakistan, not the people, is the country that ginned up the Taliban in the first place”

The other key factor that looms insidiously in both Armstrong’s and Chayes’ analysis of the situation in Afghanistan is the role that Pakistan has in their neighbour’s governance.

“Pakistan, and I mean the military, the de facto rulers of Pakistan, not the people, is the country that ginned up the Taliban in the first place. They are the ones who reconstituted the Taliban around 2003. And they are the ones who provided nuclear technology to North Korea and Iran. This is an exceedingly dangerous country that is getting missed on the global stage,” states Chayes.

Armstrong wholeheartedly agrees. “Pakistan has been waging a proxy war against Afghanistan ever since the Soviets left. Where did the Taliban come from? They came from Pakistan. Where do they stay now? They stay in Pakistan. Whose airports do they fly out of when they’re going to these peace talks? Pakistan airports. And Pakistan keeps cutting deals to make sure the government of Afghanistan cannot function. On top of that, the warlords and tribal chiefs have no interest in working with the government. That old expression, ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand,’ certainly applies.”

The biggest question now is what is going to happen to the Afghan people, most especially those people who are known to have helped journalists and others ‘friendly’ to their cause – the fixers and the interpreters – those Afghans who wanted the world, through the eyes and ears of outside reporters, to hear their story.

“I think that at the moment men’s lives are more at risk than the women’s. Any male who has worked with the previous Western-supported Afghan government in any capacity, or who has worked in the police or military, or are relatives of people who did, their lives are at risk. And while women will be oppressed and certain prominent women targeted, I don’t believe that you are likely to see the mass slaughter of Afghan women,” Chayes says.

Armstrong, however, is worried about the future of the Afghan women, many of whom have attained successful careers as lawyers, doctors, pharmacists and teachers after the Taliban were ousted by U.S.-led forces in 2001.

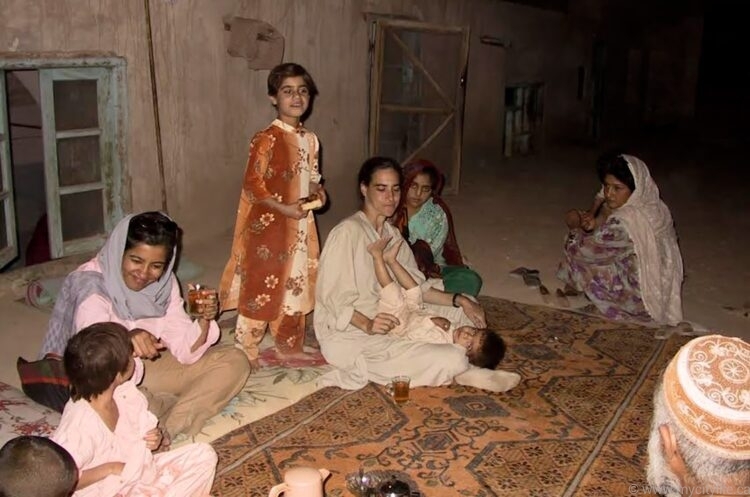

During the previous Taliban rule, women had virtually slid backwards into the Dark Ages. Young women were not allowed to attend school, and women in general could not leave their homes unless accompanied by a husband, brother or son. Windows were painted over so that the women in the household could not be seen.

“The women thought that their world had ended, and for them it had, because the Taliban took no discussion. To disobey the Taliban was to die,” Armstrong states. “A woman who was caught with a man who was not her husband, brother or son was taken to the stadium and tossed to the ground where Taliban men would make a circle around her and throw rocks at her until she was dead. The Taliban rule is, you must not throw a rock so big as to kill her quickly.”

But once the Taliban were ousted women came into their own with the power to support, sustain and nurture their daughters and sons towards a better life.

“I am hearing from these women and they are devastated and in shock with the current situation. They don’t know where to turn. And as much as you think they’d blame the people who left them, and they do, they understand that they too are part of the problem,” Armstrong continues. “Their country cannot come together under one flag, and they have to learn to do that. In the meantime, they’re dealing with 6-year-olds and 16-year-olds and elderly mothers, the same things you and I deal with. But for them, it is a matter of where they get their food when the Taliban is patrolling the streets. Their kids are no different to ours, they get croup, and forget to do their homework, and now, they’re under house arrest again.”

It is in the parsing of these realities and the acknowledgement that there are concerned people out there who do not support the rancorous vision of the Taliban, that the people of Afghanistan must tap into, while at the same time taking responsibility and accountability for what they need to do as a nation to defend, protect and advocate for themselves.

“How can the Taliban survive this latest coup in a country where 65 per cent of the population are under the age of 25 — young men and women who, if they have heard of the Taliban, certainly have never been punished by them? How can the Taliban sustain their autocratic rule in a country where universities are flourishing, where people are using the Internet to find out that other people don’t live like this?” Armstrong asks. “And these young people are finding out that the Taliban version of Islam is baloney. There’s nothing in the Quran to support what the Taliban are doing.”

With new threats from the terrorist group ISIS-K, a group believed to be even more militant than the Taliban, permeating the already volatile Afghanistan situation, global citizens can no longer deny what our eyes have seen, or what our ears have heard.

Certainly, there are a vast number of Canadians who want to help the Afghan people come to Canada and live a better life.

“We already have a team in Afghanistan,” Armstrong says. “And we have finally put together a list of all of the amazing Canadian women and some men who have been contacting me saying, ‘What can we do?’ We have this huge team of hardworking, brave, experienced activists, and we’re dividing up the jobs.”

Armstrong and Chayes are both tough and willing to embrace danger to bear witness to stories that need to be told. Veteran journalists, they have literally and figuratively been in the line of fire on untold occasions. And so, their clear and unfettered passion and belief in the merit and goodness of the people of Afghanistan are such that it becomes a call to action for all of us to be champions and advocates for the Afghan people’s sustained and future well-being.

In the meantime, on August 29, a U.S. military drone blew up a vehicle in Kabul that was loaded with explosives. The Taliban has stated that they will let anyone who has the correct travel documents depart safely. The United States and 97 other countries plan to hold the militants to their word — if that is even conceivably possible.

To find out how you can help Afghan refugees on an economic and social basis, visit www.lifelineafghanistan.ca