Have we become a Society that practises ageism?

As a society, we have all been complicit in the shocking and inadequate levels of care in our nursing homes. The time to address the maelstrom of these inadequacies is now. We all need to be involved.

Each of us has, in some way, been affected by COVID-19 and its devastating impact on the world’s physical, financial, social and mental health. It is a pandemic that has touched all of our lives, from the relatively small inconveniences of sheltering in place, to the much harder realities of the egregious conditions festering in our long-term-care (LTC) homes.

In fact, the circumstances that shroud the 630 care homes in Ontario, ones that have seen 3,648 residents die in Ontario alone (as of Feb. 4, 2021) since last March, have fostered the $500-million lawsuit filed by Diamond & Diamond Lawyers. (Diamond & Diamond has joined its claims with Rochon Genova, Himelfarb Proszanski and Cerise Latibeaudiere, bringing their various class actions into one mega-claim). The statistics are both shocking and alarming. Orchard Villa, the home that the Canadian Armed Forces were sent to in order to help care for residents, reports a total of 70 resident deaths. Tendercare Living Centre has reported 73 deaths. Roberta Place in Barrie, Ont., where several of the residents are believed to have contracted a U.K. variant of the strain, has reported 66 deaths (out of 127 residents), as of Feb. 3, 2021. (Families of residents there are in the process of filing suits against the home.)

On Jan. 13, 2021, Diamond & Diamond announced a $500-million lawsuit “on behalf of victims who died due to avoidable negligence.” The suit names major long-term-care providers across Ontario, as well as the Ontario government and several municipal bodies. The Diamond & Diamond press release states that “it is the largest suit of this type that claims COVID-19 death culpability by multiple branches of government.”

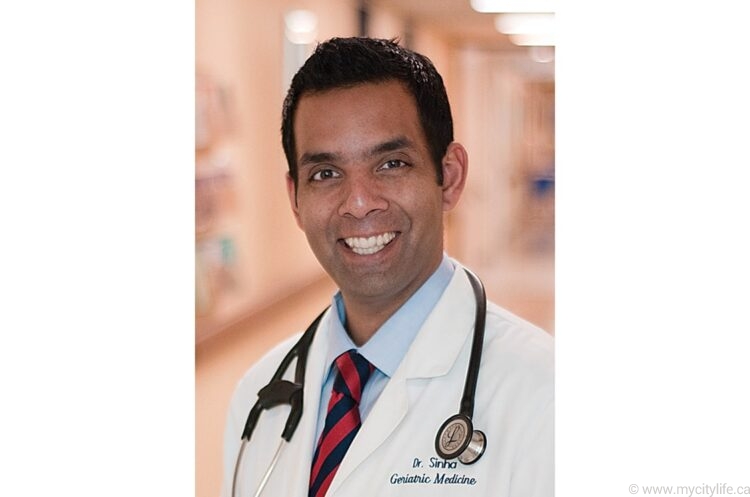

“I wonder how people feel right now about getting older, especially, when, as a society, we realize that we have all been complicit in what’s turned out, frankly, to be a senicide” — Dr. Samir Sinha

“The first class-action lawsuit was initiated in March (2020), when we started to see the first wave of deaths in these long-term-care homes,” states Darryl Singer, Diamond & Diamond’s head of commercial and civil litigation. “Because our firm already had a reputation for handling negligence cases in nursing homes, not related to COVID — you would be shocked at how much negligence there is in these homes — we were approached by several claimants. The first wave of COVID in these homes did not surprise me. I know the reasons why the first wave happened, and it is not what the nursing home operators would have you believe. But, quite frankly, I am shocked and saddened by this second wave, because these homes knew what happened in the first wave, they knew the allegations that the existing lawsuits were making against them as to why there was such a problem in the first wave. So, you would think that in the six months between the slowing of the first wave and the beginning of the second wave, that the owners, managers and facilitators at these homes would have said to themselves, ‘Let’s make sure this doesn’t happen again; let’s get prepared for the second wave.’ But, unfortunately, they didn’t do that. In fact, they have doubled down on their negligence and incompetence, which has led to the second wave. By the time this is over, there will likely be more deaths in these homes than there were in the first wave.”

You only have to speak to someone who has lost a loved one in long-term care due to COVID-19, to get a sense of just how devastating these losses are. Realistically, yes, a person who is in their 90s, or someone who is frail and vulnerable, is expected to succumb at some point, if only from natural causes. But not like this: not pressed to the window of their room, completely alone, possibly hungry, thirsty or in personal discomfort because there just aren’t enough staff to administer the proper care.

Giovanna Costa Fazari lost her beloved grandmother on April 6, 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19. An incredibly painful and hard-to-bear six days later, Fazari also lost her grandfather due to COVID-19. Both were residents at a long-term-care home in Mississauga, Ont.

“I was super close with my grandparents; I spoke with them every day. They were my favourite people in my entire world,” Fazari says. “They were loving, caring and funny, your typical nonna and nonno. I just could not ever imagine my life without them, so it is extremely hard to bear,” Fazari says.

Fazari, who was expecting her second child at the time, would stand outside the long-term-care home that her grandparents were in, with her toddler son in her arms and her husband beside her, and talk to her grandparents over the phone as they peered out their window.

“It was very sad. My son was only two at the time, and he didn’t understand why he couldn’t see his great-grandmother, why we couldn’t go into the building,” Fazari says.

How did we get to this place, mired in a situation where we, as adult children and grandchildren, cannot be of service to the people who took care of us in our formative years? It is a complex situation that lays blame at the doors of institutions, the governments and, in reality, all of us, for not doing something sooner about a system that we knew has been broken for years, if not decades.

It is no secret to any of us that our long-term-care homes, both their actual physicality, as well as their staffing and medical protocols, have been in dire need of a major overhaul for a really long time.

Dr. Patricia Spindel, speaking for Seniors for Social Action, Ontario, identifies three key concerns that she says are of issue in long-term-care homes.

“First of all, that there are no alternatives for older adults besides an institution or very poor support through home care,” Dr. Spindel says. “If you end up in the hospital, and you’re ready for discharge, your only choices are very little home care, or an institution, if long-term care is needed. That is completely unacceptable; we need to have much stronger home care support that is tied to people’s actual needs, so that they can stay at home. If that’s not viable, we need to have small not-for-profit-operated group homes, staffed condominium programs, staffed apartment programs, all staffed at the level that people need. The government is currently paying $182+ a day per person in long-term care, so if you multiply that per diem by six ($1,092), you could have a not-for-profit group home, for example. It’s an absolutely doable solution, but there is no political will to do it. Our group also believes that there needs to be comprehensive inspections, with tough sanctions imposed for repeated violations of the Long-Term-Care Homes Act (2007) and regulations. But you can’t do that unless you have alternatives, because, if a licence is revoked, there is nowhere to put people. Finally, the profit motive is a huge problem. In an article in the Toronto Star on January 20, 2021, Toronto Star references a statement made by Dr. Nathan Stall, a geriatrician at Mount Sinai Hospital, in a report from the science table that advises Premier Ford. ‘Homes with for-profit status had outbreaks with nearly twice as many residents infected … and 78% more resident deaths … compared with non-profit homes.’ That is just not acceptable. If the three underlying root causes that I mentioned were addressed, it would begin the process of fixing long-term care in Ontario. Currently, Canada pays 0.2% of its gross domestic product on home care, which is one of the lowest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, and that is ridiculous.”

So, what exactly are the differences between the for-profit and not-for-profit long-term-care homes?

Of the 630 care homes in Ontario, 57 per cent are for-profit and 27 per cent are not-for-profit. (Source: Richard Warnica, Toronto Star, Jan. 26, 2021.) What appears to be one of the major sticking points with advocates against for-profit homes is that the corporations who own these homes do so within facilities that are cramped and outdated.

“The owners of these properties view the homes as real estate investment trusts. They shove old people in there and then receive incoming funding, as well, from the government, from you and me,” Dr. Spindel says. “Many of these homes don’t even have air conditioning or clean facilities. They ask the government for more money to do the renovations, such as installing air conditioning, and Doug Ford falls for it. They have continued to get even more funding from the provincial and federal governments during COVID-19, at a time when these same corporations are paying major dividends to their shareholders.”

However, when talking about for-profit versus not-for-profit, Singer says it is important to understand that the not-for-profit sequitur doesn’t necessarily mean that no profit is being made.

“Not-for-profit just means that it is not a corporation that pays dividends to shareholders, but there is still an element of profit under these terms of management,” Singer says. “Some of these not-for-profit homes contract out to these for-profit companies, and they say, ‘We will pay you a certain amount of money to run this home.’ So, obviously, everything that these for-profit homes can do to keep their costs down is more money in their pocket. But it doesn’t really matter in the end. Whoever is operating these facilities is trying to do so for as little money as possible, which means cutting corners on stockpiles of PPE, emergency planning and reconstruction of older facilities. Poor ventilation, and three and four residents to a room are also problems when you refuse to have isolation rooms during COVID-19 outbreaks.”

“It’s hard to say exactly what things need to change when it’s the whole foundation that has crumbled” — Giovanna Costa Fazari

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of geriatrics at Sinai Health and the University Health Network in Toronto, points out that trying to disperse for-profit in favour of not-for-profit is not that cut and dried.

“One of the things that my colleague at Sinai Health, Dr. Nathan Stall, and I point out is, it’s very easy to say for-profit is evil, and not-for-profit is good. When you do head-to-head comparison of for-profit provision of care in long-term-care settings versus a not-for-profit or municipal or publicly provided care, you tend to see better quality outcomes, including lower rates of death; that’s 100 per cent clear. But what I think you see in Ontario is, the story gets greatly exaggerated because the majority of the homes in Ontario are owned or managed by for-profit providers. These are older, outdated homes, and what Dr. Stall’s research shows is what significantly increases a resident’s risk of dying from COVID-19 tends to be homes that have rooms with four beds.”

Dr. Sinha, who in 2014 was named as Canada’s most compelling voice for the elderly, has been reduced to tears from what he sees is deep societal ageism. “I care for the population that represents 96 per cent of Canada’s deaths; it’s been absolutely frustrating,” he says. “When Canadians 65 or older represent 96 per cent of our deaths, and when over two-thirds of our deaths have occurred in long-term-care and retirement-home settings, it is demoralizing, especially when definitive actions could have been taken at so many points during this pandemic to protect this cohort. If COVID-19 was a disease where 96 per cent of its victims were under the age of 15, how different would our society have reacted? I think we would have reacted very differently, and I find that deeply disturbing because, as Canadians, the vast majority of us are going to make it into that 60-plus age group. We’re pretty much guaranteed that, unless something takes us before the age of 60. Our average life expectancy is forecast to be, on average, 82 years of age, and so, many of us are going to become older Canadians. I wonder how people feel right now about getting older, especially, when, as a society, we realize that we have all been complicit in what’s turned out, frankly, to be a senicide.”

Both Dr. Spindel and Dr. Sinha acknowledge the realities around the troubling testimony of Dr. Stall to the Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission around residents being given unneeded drugs in long-term care homes.

“Residents were being drugged with antipsychotic medications to keep them quiet, and you know what? It raises an interesting question; these homes weren’t allowing even people with power of attorneys into the facilities, so who was ordering these antipsychotic medications that they were putting people on to keep them quiet when there was nobody there to give permission or to refuse permission? Somebody was guilty of prescribing and administering these medications without informed consent, and that’s assault,” Dr. Spindel states.

In a press release dated Oct. 1, 2020, the Ministry of Long-Term-Care Ontario acknowledges that it received a statement of claim in the Robertson et al. vs. Ontario et al. matter.

The statement goes on (in part), to say that “We have seen how quickly this virus spreads, and community transmission remains a serious threat to longterm- care homes. That is why our government has continued to make additional resources available to prevent and contain the spread of COVID-19, including $1.38 billion in support for long-term care. We have moved aggressively to address staffing shortfalls, including a commitment to hire 27,000 new workers and provide an average of four hours of direct daily care.”

Part of the spending plans to improve long-term care needs is also included in the ministry’s Oct. 1, statement: “We are also investing $30 million to allow long-term-care homes to hire more infection prevention and control (IPAC) staffing, including $20 million for additional personnel and $10 million to fund training for new and existing staff, allowing homes to hire over 150 new staff.”

These promises were made in October, but as is highly evident by what is going on at Roberta Place, as well as other long-term-care homes in Ontario, it feels like it’s too late, way too late.

In the darkest days of COVID-19, as the second wave of breakouts occurred in long-term-care homes, families and physicians began talking openly about finding people who were dehydrated and needed help being fed.

“In homes that supposedly had stable staffing, when closer scrutiny was applied, the staffing was actually being filled by several different agencies who were sending in temporary nurses and personal support workers (PSWs) who were going from home to home. Not only did that heighten the levels of transmission from home to home, these temporary fill-in staff did not have a relationship with the residents, a fact that exacerbated the loneliness and isolation, and oft-times lack of specialized care for loved ones,” Dr. Sinha says.

“We are all only one stroke away from being in one of these homes” — Dr. Patricia Spindel

“These facts help to underlie why people didn’t just die of COVID-19 in these situations. Imagine yourself in a situation where, all of a sudden, the nurse who knows your mom really well, that personal support worker who has been caring for your mom every day since she got admitted, knows what she likes, knows what she doesn’t like, all those sorts of things, all of a sudden, the familiar staff isn’t there, during a time of crisis, a time when a person needs comfort and is likely experiencing more challenges with their care. Now, all of a sudden, you have random people coming in, trying to do their best to help stabilize the situation, but they don’t know the familiar phrases to comfort your mom and encourage her to eat. The PSW or nurse doesn’t know the usual jokes to get a smile out of your mom, or how to coax her to get bathed and dressed. All of a sudden, it is overwhelming because, when there isn’t sufficient staffing, it’s hard to make sure that each of the residents gets the time they need for their personal care and their nutrition and hydration needs to be met. One centre is a prime example of the terrible negligence that has been happening during COVID-19: people were banging on the walls, banging for water, banging for food; families don’t make these stories up. The sad part is, when I see that death rates in some of these homes are double or triple the current overall rate of 18 per cent, it tells me that there’s more going on in a home.”

It is this kind of situation that a group of Ontario doctors has called a “grave humanitarian crisis” as they issued a list of demands on how the province can improve the care of vulnerable residents (Source: Tyler Dawson, National Post, Jan. 26, 2021.)

So, realistically, what are the steps we can take in the short term, in fact, immediately, to effect the much-needed changes? We need look no further than British Columbia, to Dr. Bonnie Henry’s forward-thinking action plan.

Recognizing that outbreaks of COVID-19 in long-term care homes often happened through community spread, Dr. Henry, provincial health officer for British Columbia, changed the funding formula and hiring practices across all long-term-care homes in the province, ordering both for-profit and not-for-profit to pay staff at the highest equitable union rate, which includes 18 days of paid sick time. In this new arrangement, staff who might previously have worked part time at multiple homes (as part-timers, their pay was so low that they had to work at more one than one facility to make a living) had the opportunity to choose the home in which they wanted to work.

“If there is no full-time work available, the staff still get their full-time salary. The government is even offering to pay for training costs for new hires coming into the system,” Dr. Sinha says.

In a report that the Seniors for Social Action presented to the Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission, the list of recommendations proposed includes that, in concert with the development of alternatives to the institutional sector, a more rigorous inspection system be introduced incorporating forensic audits, especially in problematic facilities; a prosecution policy; and licence revocations. A recommendation to pursue criminal action when substandard or criminally negligent care was noted, as well as the implementation of an oversight mechanism to ensure physicians do not abandon, chemically restrain, fail to treat residents or order necessary hospitalization, was strongly recommended.

Singer agrees that “there is no follow-up on complaints; and there has to be. There has to be some teeth to any enforcement mechanism, because right now, the operators don’t care, because there’s no consequences to them, to what they are doing. So, there needs to be consequences, there needs to be accountability.”

Is the current situation in our long-term-care homes a case of too little, too late?

“It’s hard to say exactly what things need to change when it’s the whole foundation that has crumbled,” Fazari says. “There is a lot of work ahead for the government, the owners of these care homes and the people who manage them, to make these homes amicable, livable, clean and safe places for our vulnerable population.”

No matter what the outcome of this class-action lawsuit is, there is one thing that is legally and morally clear: It is our duty as a society to not only be aware, informed and cognizant of what is going on in our long-term-care homes, but also to be advocates for our elders, whether they be our family, friends or neighbours. There will come a time when each of us will need a helping, caring hand.

“We want to make sure that, at the end of the day, there are major changes, both in how the province regulates and enforces, and how the operators operate,” says Singer. “We are hearing that all residents in nursing homes will be vaccinated by the end of the month (February), and hopefully everyone in the country by August or September. But that doesn’t mean that there’s not going to be a third wave. We already know of two particular variants to this virus, but we don’t know the repercussions yet. It’s too early to tell. We also know — all the medical people and health professionals are saying it — that, as a society, we need to get used to this concept of pandemics, because there’s going to be more of them. We need to be aware that the families of these people who are in these homes are the most vulnerable people in the province, outside of a hospital setting. It is up to us to make sure that they are protected.”

“We are all only one stroke away from being in one of these homes,” Dr. Spindel says.

For information or to become a part of the Diamond & Diamond class-action lawsuit, call 1-800-567-HURT.