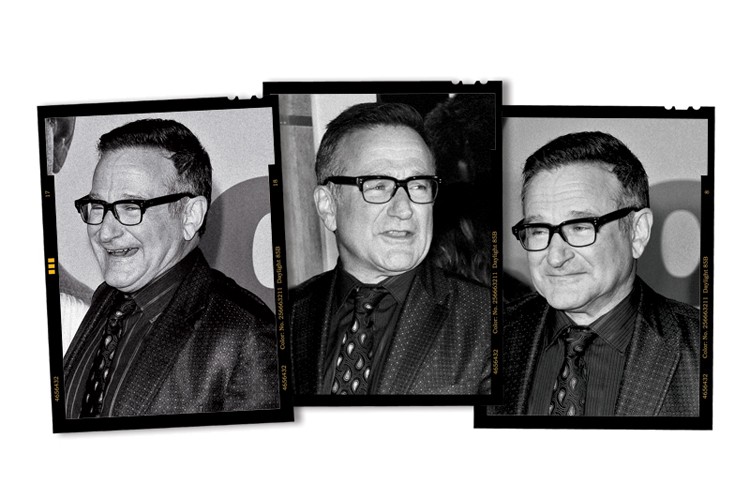

The Sad Clown – A psychologist’s take on the Robin Williams tragedy

Not long ago I encountered the exceptionally talented comedian and actor Robin Williams in a New York City restaurant. In his typical high-energy, seemingly casual way, he said to me: “Oh, Dr. Judy, I need a psychologist.”

“Call me anytime,” I quipped back.

Half of me thought he was just jokingly relating to me by what I do, but the other half thought he was being truthful, given what I knew about his history of emotional issues.

I didn’t hear from him, and now, after news of his tragic suicide, I’m painfully aware of how serious his remark was.

All too often a cry for help is masked, or unheeded.

According to his publicist, Williams was battling severe depression. Williams’ wife, Susan Schneider, confirmed this, and added that he was also experiencing anxiety and early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Though she insisted he was now sober, Williams had a long history of addiction, from which the addict is always in recovery.

A trio of problems — addiction, depression and a physical disease — can certainly add up to overwhelming hopelessness and drastic responses to end the pain, even if research doesn’t prove that patients with Parkinson’s are any more suicidal than those without the disorder. Yet, for a performer like Williams, who banks on fluid speech and exaggerated movement, facing such a diagnosis might be too much to bear.

Wisely, Schneider made a plea for troubled souls to seek help: “It is our hope in the wake of Robin’s tragic passing, that others will find the strength to seek the care and support they need to treat whatever battles they are facing so they may feel less afraid.” Although Williams had checked in at a Minnesota rehab centre and was receiving treatment before his death, his stay may have been too brief.

Despite marvelling at Williams’ lightning-paced ad-libbing, the psychologist side of me always worried that his over-the-top energy belied a darker side and a serious underlying condition. In my view, warning signs were evident even eight years ago in an ABC News interview with Diane Sawyer when Williams referred to standing on a precipice and hearing a quiet little voice say “Jump.”

Williams’ stream of consciousness and free association were intrinsic to his comic genius. But such over-the-top talk is also symptomatic of cocaine use, to which Williams admitted in the 1980s. In the psychology profession, there is another possibility, where symptoms of “pressured speech” and “word salad” indicate a manic state. When combined with reported depressive bouts, the condition is called bipolar.

The term “bipolar” — which in recent years replaced the diagnostic term “manic depression” — is characterized by severe highs and lows and disabling seesaw swings of moods, energy and activity. People in a manic phase have so much fun and are so entertaining they don’t want to dull that with medication that would even out their mood and moderate their behaviour. Yet, the thrill of great highs extracts a high price when the opposite painful pole of depression hits. Suicide is always a danger.

The question I’m always asked is: Why would anyone who seemed to have so much to live for want to end their life? The answer is severalfold.

For one, no one knows the private pain another person suffers, even if they seem to have it all. Failure at work, rejection in love and other fears can trigger deep desolation that leads to the desire to escape it all and end the pain. Making matters worse, impulses can be totally out of one’s control when ruled by chemical imbalances in the brain, which occur with drug and alcohol abuse or certain mental and physical conditions. Another problem is that the person suffering may hide his/her true self.

Psychological studies show that comedians often use humour to cover underlying despair. One survey of 532 comedians found they have a much lower ability than ordinary people to focus and control their moods and a much higher rate of impulsivity and unusual experiences. British researchers attributed these results to creative talent, but also associated them with personality conditions.

More than five million people are estimated to similarly suffer from bipolar disorder, including celebrities Carrie Fisher (Star Wars) and Catherine Zeta-Jones (The Mask of Zorro). Those with bipolar disorder can lead productive lives — with treatment. An effective ongoing “maintenance” plan includes a combination of “talk therapy” and medication to stabilize moods and behaviour. Education about treatment, prevention, early diagnosis and the need for more funding for research and programs is crucial.

In playing a psychiatrist in the film Good Will Hunting, Williams advises Matt Damon’s troubled character to taste love, happiness and life instead of using defence mechanisms. He calls the Will Hunting character a “genius,” empathizes that “no one could possibly understand the depths of you” and advises him to talk about who he really is. The celluloid Williams could have been talking about himself. Had he taken this wisdom to heart, he might still be alive and with us today.

GUEST PSYCHOLOGY EDITOR

Judy Kuriansky is an internationally known clinical psychologist and relationship counsellor and the chair of the Psychology Coalition of NGOs at the United Nations. She is also a TV and radio personality and the author of many books, including The Complete Idiot’s Guide to a Healthy Relationship.

www.DrJudy.com

No Comment