LETHAL DOSE, VAUGHAN AND TORONTO FACE OPIOID CRISIS

Two people in Ontario die every day of an opioid overdose. City Life Magazine uncovers the opioid epidemic as it migrates eastward, tearing its way into our communities and homes by way of substance abuse and prescribed pain management.

Over the course of three years Joe* overdosed several times—six to be exact—and died twice. He needed to be resuscitated on two occasions when his heart stopped after shooting doses that were, unbeknownst to him, cut with fentanyl. The drugs had Joe in such a terrifying state of mind that he often had suicidal thoughts. “I knew the drugs were killing me slowly, and that gave me comfort,” he admits.

When the Vaughan resident was 16 years old he began smoking marijuana and experimenting with cocaine to fit in with the cool kids. A dangerous cocktail of low self-esteem, depression and a deep desire to run in the popular circles had the high-schooler headed down a dark path. After a while the high didn’t faze him.

Shortly after beginning his first part-time job at a local grocery store at 19 he was introduced to opiates by his co-workers. In search of a better high, he didn’t hesitate — one oxy and he was hooked. His new drug of choice spiralled into a $330-a-day debt that he found himself working seven days a week to support.

“All I had to do was call them to get more,” says Joe. “It was easier to get than weed.”

While Joe began with OxyContin, which he snorted, that led to shooting up heroin multiple times a day. It was a year and half before either his family or his long-time girlfriend caught on to what was happening. It wasn’t until a year and a half later that the 22-year-old accepted it was time to seek help.

“Two of [the overdoses] happened when I was at home, and my little brother used to come in and find me,” says Joe. “My second overdose threw me into a coma for three days, and what scared me was that it didn’t scare me.” He recalls walking out of the hospital and getting back to the same habits.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, is similar to morphine but can be up to 100 times more potent. Initially developed in the 60s for operative patients in severe pain, today it is more loosely prescribed for chronic pain — and the fentanyl on the streets is illicitly prepared. Within the last two years specifically, Canadian recreational drug users have been warned of the possibility of everything from cocaine to heroin being laced with the much cheaper and more easily accessible fentanyl.

“We all have a role to play in preventing people from becoming dependent on opioids, as well as supporting those who are affected by opioid use disorder,” says Dr. Eric Hoskins, Ontario minister of health and long-term care, in a statement this past May. “In Ontario, we have been clear about the need to urgently address the opioid crisis.”

“In the last five years we’ve really seen an increase in opiate addictions, and it hits those from all walks of life,” says Cindy Cepparo, program director at the Vitanova Foundation. Vitanova is a not-for-profit addiction recovery centre in the heart of Vaughan that offers addiction-related services to individuals and their families. Founded in 1987 by Dr. Franca Damiani Carella, Vitanova has successfully treated over 15,000 individuals in the community and beyond.

“In our experience, opiate users don’t come to us after a year or two; they come to us after years of abuse,” Cepparo adds — a testament to the intense physical and mental dependency on the drug of substance abusers.

After his sixth and final overdose Joe had had enough. He had hit rock bottom and decided he wanted to get help, regardless of the joint pains, cold sweats and muscle aches he knew lay ahead. The then 22-year-old admitted himself, with the support of his family, to Vitanova and started on the road to recovery. “I wasn’t going to go unless I was ready, and if I was forced in there it would have just been a waste of time for everyone,” says Joe. “They say our emotional and mental state stops when you start using, so that was basically a 16-year-old going into rehab at 22.”

Joe stayed at Vitanova for six months, five months longer than he had initially been willing to stay. “You realize how important it is to disconnect from the outside world and begin to discover yourself,” he admits. Cosimo Schiafone, addiction support worker and facilities manager at Vitanova, says the key to the program at the rehab facility is total abstinence. “While they’re here, they not only learn valuable coping skills for their addiction, but we also focus on the traumas or emotions they’ve experienced that led to the substance abuse,” says Schiafone.

Opioid abuse is not just a western Canadian issue, as often portrayed by the media, but a nationwide crisis. It is an epidemic that has migrated eastward, not only to the province of Ontario, but also to York Region. Many would consider Joe to be lucky; after numerous dances with death, surrounded by family and a supportive partner, he was able to reach sobriety.

But many stories don’t end like Joe’s. According to Public Health Ontario’s online opioid tracker, fentanyl alone made up 33.3 per cent of deaths caused by opiates in the York Region in 2015, second to codeine, which accounted for 36.7 per cent of deaths, followed by oxycodone (which includes OxyContin), which made up 30 per cent.

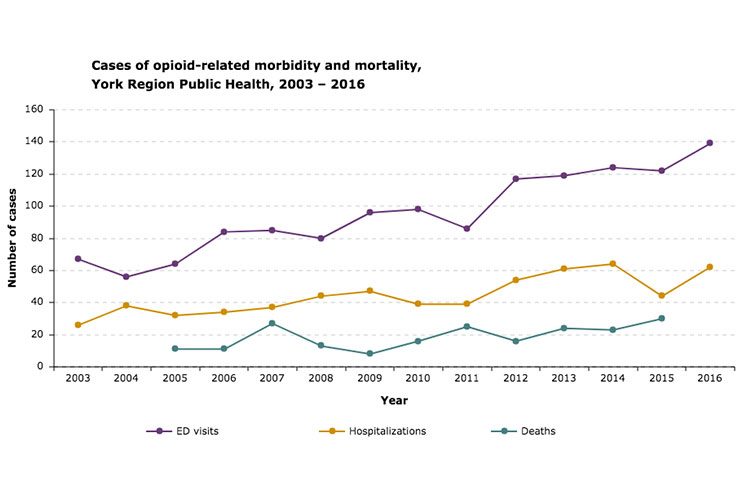

Opioid use skyrocketed between 2015 and 2016. According to the tracker, York Region experienced a 14 per cent increase in emergency department visits and a 40 per cent increase in hospitalizations due to opioid poisoning during that period.

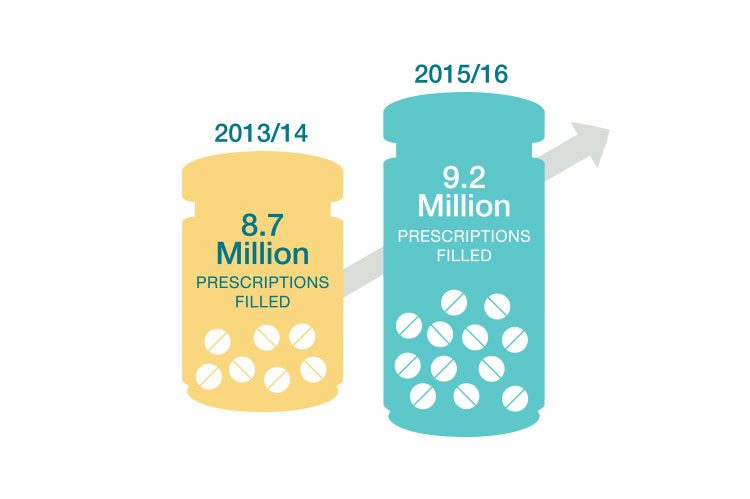

The statistics are alarming, but the problem doesn’t end with illicit street drugs. According to Health Quality Ontario, nearly two million people in Ontario fill prescriptions for opioids every year — which translates to into one in every seven Ontarians, or 14 per cent of the province’s population. “Canada is the second highest consumer of opioids, and we have a great deal of morbidity and mortality from opioids,” says Dr. Rocco Gerace, registrar at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO). “Part of the opioid problem is related to physician prescribing, and that’s our responsibility.”

The provincial opioid tracker doesn’t give much indication as to whether or not hospitalizations and overdoses were due to recreational drug abuse, accidental prescription overdose or an addiction stemming from prescribed pain medication that then resulted in overdose.

“If we ask the right questions, we may find back in the day that people had an injury and may have been exposed to an opiate,” says Schiafone. “More and more cases are coming out where we realize that the addiction began with a prescription from a doctor.”

In an attempt to combat this growing issue, the CPSO is committing to a wide-ranging strategy, with goals to facilitate safe and appropriate prescribing and reduce the risk to both patients and the public. This includes a four-step approach to guide, assess, investigate and facilitate education, actions that Greg Carney and his daughter Melissa say are happening far too late.

It was just over a year ago when Greg found his wife, 60-year-old Ann Carney, unresponsive on the living room couch. Ann had accidentally overdosed on her prescribed fentanyl patch, a toxicology report would reveal months after her passing.

It all started approximately a decade before her death, when Ann went in for a routine surgery, and complications led to chronic pain in one of her legs due to nerve damage. Ann’s leg was sensitive to touch, to clothing and even to sunlight. After numerous attempts to repair the damage through surgery with no success, she was referred to a pain specialist at a local hospital.

For years, Ann tried various painkillers, including fentanyl in a 120-mcg patch. Over the initial years of her treatment she would experience sudden onset blackouts, which always went undiagnosed by physicians and emergency room doctors — no one could connect the dots, according to her widowed husband, Greg.

He says it wasn’t until a specialist at Sunnybrook Hospital took a look at her daily menu of medications that she was warned to lower her dosage of many of the prescriptions, including fentanyl. Although concerned that it was the only thing that was helping to alleviate some of the pain, Ann took the advice of Sunnybrook doctors and her family physician and slowly cut back to 50 mcg of the fentanyl and the other prescriptions for the remainder of her years.

A week before she passed, Ann started having increased episodes of blacking out. When she went back to the doctor for the issue he ordered some blood tests, which she scheduled for the following day — she would not make it to that appointment. Ann died the next morning.

“I had so many questions, like what caused the overdose if she was taking the prescription as prescribed?” says Greg. “She didn’t deviate from it at all.” Greg shares that Ann had twice the legal dose of fentanyl in her system. It’s unclear who should be held responsible for Ann’s death, but what is clear is that the drug is dangerous and there needs to be more stringent regulation in place.

“Fentanyl is not to be fooled with, and should only be used by people that are already dying,” says Greg. “The coroner’s office should also have a better tracking system for opioid death and make sure there’s a distinction between prescribed doses and street drugs.”

Melissa agrees with her father and adds that the most important thing right now is awareness.

Greg and Melissa are determined to continue advocating for better prescribing practices. The father-daughter duo will also continue raising awareness of the dangers of opioids and challenging their local and provincial governments to make a move.

“There’s no question that there are indications for opioids, and there’s no question that their use in terminal pain is critical and will remain critical,” says Dr. Gerace. “But in terms of chronic pain, there are multiple other modalities that could be used, and I think it’s fair for patients to question if they’re given prescriptions for large amounts of opioids, because that is one of the things that creates problems.”

The registrar stresses the importance of the public being their own advocates as well, urging them to contact the Public Advisory Service at the CPSO with any questions they may have. “It’s a complicated issue and we have to bring all of the stakeholders together in order to effect a solution that will protect the patients and the public,” says Dr. Gerace.

Rehabilitation centres that place an emphasis on abstinence worry that too many resources are allocated to harm reduction as opposed to harm prevention initiatives. While Vitanova is only partially funded by the Ministry of Health, its domiciliary program isn’t government funded at all, and Schiafone admits he is discouraged to see money being pumped into resources that don’t subscribe to the same abstinent approach.

Dr. Gerace says that as a society it is our responsibility to protect patients who are vulnerable, and things like our supervised injection sites do so. “They prevent transmission of infectious diseases and they’re also there in the event that someone uses inappropriate amounts of opioids and needs some kind of resuscitative intervention,” says Dr. Gerace.

Another nationwide initiative includes a free-of-charge naloxone kit. During an opioid overdose the drug affects the part of the brain that regulates breathing, causing severe respiratory depression and death. Naloxone is the opioid toxicity antidote, temporarily availing the overdose.

The kit can be picked up at participating local pharmacies, no questions asked. “I think it’s important people know, if they’ve had to use naloxone, that it’s not a cure; they have to go to the hospital because most of these drugs last longer than the naloxone,” says Dr. Gerace, who explains that the potency of the opiates can vary.

It seems clear that whether there is a substance addiction present or the drug is used as prescribed, opioids present an immediate threat to our communities and to our families.

In early 2016, in partnership with the York Regional Police, Addiction Services York Region, community pharmacists and physicians, and York Region Public Health established an opioid education working group to address the issue of opioid use and misuse in York Region through community education. Its initiatives include the over-the-counter naloxone and the Fentanyl Patch 4 Patch Return Program — a small but significant step in the right direction.

Opioids robbed Joe of his youth, strained his relationships, put him in debt and tormented him physically and emotionally. Now, 17 months sober, Joe is grateful for another chance at life. The 24-year-old is hyper-focused on keeping up with Vitanova’s aftercare program and staying connected to his counsellor.

Statistically, chances of opiate addiction relapse are higher than those for any other drug addictions, but Joe refuses to fall into the statistic.

A month prior to going to press with our story, Joe shared that the ex-co-worker who initially introduced him to opiates had died by suicide. Since becoming sober, Joe hadn’t had any contact with the now- deceased man.

*Name has been changed to protect the identity of the individual

www.vitanova.ca

www.cpso.on.ca

www.publicahealthontario.ca

www.hqontario.ca

No Comment